In 2008, I was attending an all-boys Catholic high school at the same time that the national press’s reporting on priest molestation cover-ups reached a fever pitch. One day, in religion class, the school’s resident Franciscan monk was on the verge of tears.

“It’s just terrible, boys,” he said. “The media in this country are relishing in an opportunity to smear the Church. You don’t see them reporting on all of the great things that it does for communities. They just focus on the bad things. There might be, I don’t know, 1 percent of priests who have committed this horrible sin. One percent out of hundreds of thousands. How is this fair?”

I thought about that speech a lot during Spotlight, the fascinating, stomach-churning political thriller by Tom McCarthy (The Visitor, The Station Agent) about the Boston Globe’s investigation into local allegations of abusive priests. At the time, I was conflicted over what the monk said; he was so sincere, after all, and his angst grew out of his intense love of his religion and of the immense good that he had seen it accomplish throughout his life. In the film’s portrayal of the Church establishment, many people of differing status echo what he said, almost exactly: “It’s just a few bad apples,” they say. But during the course of this riveting journalist-conspiracy thriller (which alleges that more than 6 percent of priests have molested children), it becomes crushingly apparent that these well-intentioned deflections, over time, have created environments that enable celibate priests to rape without punishment. As a result, the rationalizations of Catholic communities across the world, as much as the guilty priests themselves, have caused thousands upon thousands of broken lives, early suicides, and children abused both spiritually and physically.

One bemused defense attorney played by Stanley Tucci sums it up best: “People say that it takes a village to raise a child. Let me assure you, it also takes a village to abuse one.”

Spotlight somehow walks a tightrope between entertainment and harsh questions about the nature of power, about the psyches of the guilty priests and of the religious communities in which they operate. It tackles these heavy, polemical subjects in a way that does justice to the victims without sentimentalization or exploitation, while also acting as an engrossing thriller to casual movie-goers. In its own way, it is a masterful piece of journalism itself. It excites with the twists of the conspiracy and disgusts with the constant hum of moral outrage.

And it begins so unassumingly. At the Boston Globe in the late 1990s, a longtime editor retires and a new up-and-comer, Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber), comes in to shake things up. First on his agenda: a handful of priest molestation allegations that have been basically ignored by the local press. As a Jew, Baron is an outsider in the almost entirely Catholic Boston area, and, as such, is immediately chastised for a perceived anti-Christian agenda. Just as the Franciscan at my school tried to ignore the terrifying ramifications of priests who prey on impressionable children, the city of Boston as a whole chose to sweep the allegations under the rug in the interest of keeping their spiritual lives intact—a choice that, through the next two hours, will reveal itself to be inherently selfish and reactionary.

Baron, despite protests from local leaders and a quietly threatening meeting with Boston Archbishop/Cardinal Bernard Law, assigns the investigation to a Globe team called “Spotlight.”

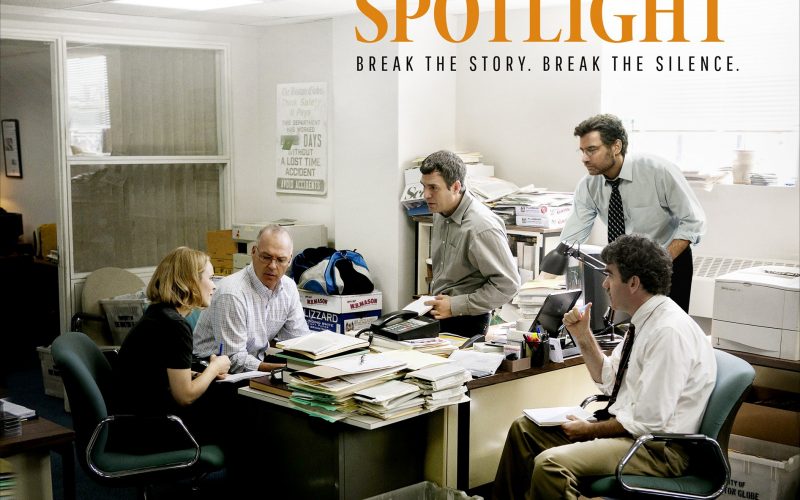

The slow unraveling of the Church’s deceit by this team makes up the majority of the film, and it is fascinating and horrifying in equal measure. The team is made up of Spotlight editor Robby Robinson (Michael Keaton), and journalists played Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams, and Brian d’Arcy James. The team itself, in one of the best acting ensembles in recent memory, is the lead of the movie, with no one actor filling the traditional role of main protagonist. Each character brings his/her own biases and religious background to the case (all are lapsed Catholics), as well as differing relationships with the city of Boston.

It is difficult to characterize Spotlight beyond its thriller genre because it is both deeply unsettling and strangely invigorating. The full breadth of the Church’s cover-ups is brought into light in some of the most terrifying end-of-movie, pre-credit captions ever, which, among other pieces of information, list seemingly hundreds of cities from across the world that have seen their own priest molestation scandals. At the same time, the movie, beside being a brilliant piece of pop culture journalism itself, upholds and celebrates the true heroism of hard-nosed, long term investigative reporting.

Spotlight is intelligent, thought-provoking, heart-pounding entertainment. It’s not every year, maybe not even every few years, that a movie can succeed on so many levels simultaneously. Spotlight is not only a celebration of what journalism can do: it’s a celebration of film as a tool that can be wielded to inform, shock, persuade, and entertain the public, in this case all at once. It may not be formally daring or visually experimental, but it proves that sometimes a great movie can be simple, that sometimes all it takes is a complex story, well told. 5 out of 5.