Photographers capture magic of small-town libraries

LARA JO HIGHTOWER

lhightower@nwadg.com

A funny thing happened to writer, artist and photographer Sabine Schmidt on the way to finishing her book, “Remote Access,” her second collaboration with photographer Don House: She ended up running one of the small libraries that the book features.

“This job is 15 hours a week, which means the library is mainly volunteer-run,” says Schmidt on a phone call from the small St. Paul Public Library where she assumed the role of director in February. “There’s a lot of community buy-in — the number of people who work for a few hours a week to keep it going. I think that was part of what attracted me to it. This is a great example of how a community supports its library. There’s a really nice kind of laid-back, but practical, energy here that I really enjoyed. And since we’ve been spending so much time here, and since I’ve been learning so much about small libraries, I applied.”

In fact, Schmidt’s life — for almost three years now — has been primarily consumed by the study of small libraries. She and House launched their project with the intention of focusing on 50 of the smallest of Arkansas’ 200-plus libraries. But when the project became more robust than originally predicted — and more expensive, given that Schmidt estimates each library study costs around $1,000 in supplies and travel expenses— they cut that number in half. The arrival of covid-19 in March further cut the list down to 21. The final book will take a close look at these small libraries and the important place they hold in their community’s ecosystem.

Schmidt says she and House got the idea from their own personal experiences with libraries: They live in Hazel Valley, and the two avid library patrons found themselves almost equidistant from both the St. Paul Public Library and the Fayetteville Public Library. The contrast was striking.

The original intention of the project was for Don House to contribute portraits, black and white photos taken of a smattering of the library’s patrons and employees, and Schmidt would record the community around the library with her color photography. This is the Sweet Home C.O.G.I.C. Building in Sweet Home, Ark.

(Photo by Sabine Schmidt)

“We were thinking, more and more, about the importance of small libraries in small rural communities,” she says. “Especially because we also went to Fayetteville. Fayetteville, as we all know, is this fantastic, world class library. And then to come over here and see what can be done with a tiny budget but a lot of community support — it was really impressive. We started talking about what would happen if a library had to close or if a community lost its school. Sometimes we saw both in our travels. And we wanted to honor that, just kind of show what’s happening in all of these tiny places in Arkansas.”

The original intention was to create a photo book: House would contribute portraits, black and white photos taken of a smattering of the library’s patrons and employees, and Schmidt would record the community around the library with her color photography. But the duo was so moved by what they were discovering, says Schmidt, that it couldn’t be limited to short captions underneath the photos. So they added an essay component.

“They’re fairly short, but we just had to talk about what we saw and learned and experienced,” notes Schmidt. “We didn’t plan it this way, but Don’s essays, most of them, are kind of written portraits of a person who showed up on portrait day, or the driver of the bookmobile that we followed for a day, or a librarian. He wrote these vignettes, these beautiful portraits of one person, one individual. And mine are kind of like my photos — they’re portraits of the town, often with a bit of discourse into history, just kind of how I experienced the town. We just had to write about them. We couldn’t just take the photos.”

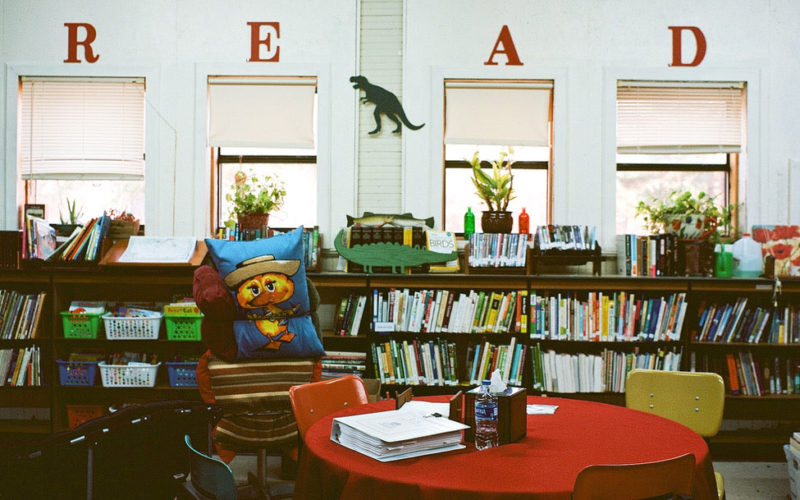

“As kids, a lot of us may have had access to a small library with a friendly librarian who lets you in, and you’re 10 years old, and she kind of steers you away from the kids’ books and says, ‘Why don’t you check over there?’” says Schmidt. “I ended up reading stuff I never knew existed, like my first John Steinbeck novel or something. So I think there’s a bit of a romantic, nostalgic aspect to it, what a librarian does for her community.” This photo was taken at the library in Stamps, but Schmidt is now the librarian at the St. Paul Public Library.

(Photo by Don House)

So what did they discover that was so compelling? Something not that surprising to Schmidt, used as she was to patronizing St. Paul Public Library: In smaller communities, the public library means so much more than a place to check out books. In many of these towns, the library was a direct lens through which to study the community surrounding it.

“Some librarians would probably argue with me on this one, but books are probably the least important aspect of a small public library,” she says. “Like the one that I’m in, and it’s probably not the only one, DVDs are so much more important when it comes to circulation, what people really want and need. Of course, it’s because internet connectivity is an issue here, as it is in many other communities. People may not have internet at home. They may not be able to afford satellite service. Audio books are still important. And just the sense that this is a community hub, where you can go and have a cup of coffee and work on a puzzle and see your friends and see your neighbors. Children’s programming is incredibly important, especially for the youngest kids that don’t go to school yet. The summer reading program that all the libraries are running this summer is very important to the community. We have one local farm that sells produce on the library porch on Fridays. Crafts activities, arts, things like that — a place for people to go and be part of their community. I think that’s the most important aspect of their libraries.”

Schmidt says there were some more sobering discoveries that changed the vision of the book once they started.

“We realized that what we’re doing is not only honoring and celebrating the library, but also getting a sense of the culture of Arkansas and the different regional cultures within Arkansas,” she says. “And that includes racism. We found out things, we saw things, we’ve heard from the librarians — every place we went to had some form of historical or present-day racism that was an incredible learning experience. And so the book is different than what we first thought it would be. It’s almost like we kind of grew up with the book.”

Because of what they learned, House and Schmidt were vigilant about including communities that represented the experience of Black Arkansans. Take Stamps, Ark., for an example, birthplace of Maya Angelou.

“While the town is a little too big, and the library’s a little too big to have originally made the list, we thought it was an important place to include,” Schmidt says. “We thought, ‘We want to know what this town is like, where Maya Angelou spent part of her childhood, where “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” is mostly set.’ We drove around and found much of what she described to still be visible.”

In recent years, many small libraries have faced harsh budget cuts that have made survival difficult. But what Schmidt discovered in her travels left her optimistic about the future of the institutions — primarily because there are so many people in the state willing to fight for them.

“Almost all of the libraries that we visited go back to one person, usually a woman or a group of women, making the decision that the community needed a library that was separate from what the school may or may not have been offering,” she says. “And that tradition actually carries on to Wrightsville, just south of Little Rock, which had access to the Central Arkansas Library branches, but there was no library near Wrightsville. A city council member named Emily Brooks worked for years talking to the Little Rock system, asking that Wrightsville be included. And she made it happen. They have a beautiful library that opened in 2013. And then there’s the truly grassroots effort of Rachel Reynolds, who moved to Fox and started the People’s Library last fall. She found an empty building, the community helped her renovate it, and she’s been getting book donations and shelving donations.”

As for St. Paul and Schmidt’s new role there: Now that the book is completed, she says she plans to concentrate on her art and her new position, which she’s finding to be exactly — and nothing at all — like what she expected.

“As kids, a lot of us may have had access to a small library with a friendly librarian who lets you in, and you’re 10 years old, and she kind of steers you away from the kids’ books and says, ‘Why don’t you check over there?’” says Schmidt. “I ended up reading stuff I never knew existed, like my first John Steinbeck novel or something. So I think there’s a bit of a romantic, nostalgic aspect to it, what a librarian does for her community.”

But, she says, as it turns out, it’s a lot busier than she expected.

“Librarians don’t have time to read, but I knew that going in,” she says, laughing. “And there’s not really any time to walk around the collections, straightening books on the shelves and lovingly dusting the houseplants. It’s a lot less quiet than I thought. This is a profession for introverts who can function as extroverts while they’re interacting with their communities, with the public. And from what I’ve heard, extroverts get a lot of energy from those interactions, and introverts need to go home and not talk to anyone for a while. So it’s a blend of that, and I love it.

“The coolest thing for me as a librarian — you have a 3-year-old coming in who can barely look over the counter, and you say, ‘Hi! What do you think about this book?’ and you get the smiles and the big eyes and the happiness, the connection that you can make that way. That’s my favorite part of the job.”

Sabine Schmidt’s photos for the book are comprised mainly of the library buildings and the communities that surround them. This one was shot in Eureka Springs.

(Photo by Sabine Schmidt)

FYI

Find the Book

“Remote Access: The Libraries Project” by Don House and Sabine Schmidt is a collaboration with the University of Arkansas’ Robert Cochran, director of the Center for Arkansas and Regional Studies, which partially funded the project. It will be published by the University of Arkansas Press. Schmidt anticipates the book will be available in the spring.

“We started talking about what would happen if a library had to close or if a community lost its school. Sometimes we saw both in our travels,” Schmidt says. “And we wanted to honor that, just kind of show what’s happening in all of these tiny places in Arkansas.” This is the old school cafeteria in Tollette.

(Photo by Sabine Schmidt)