By John LaForge

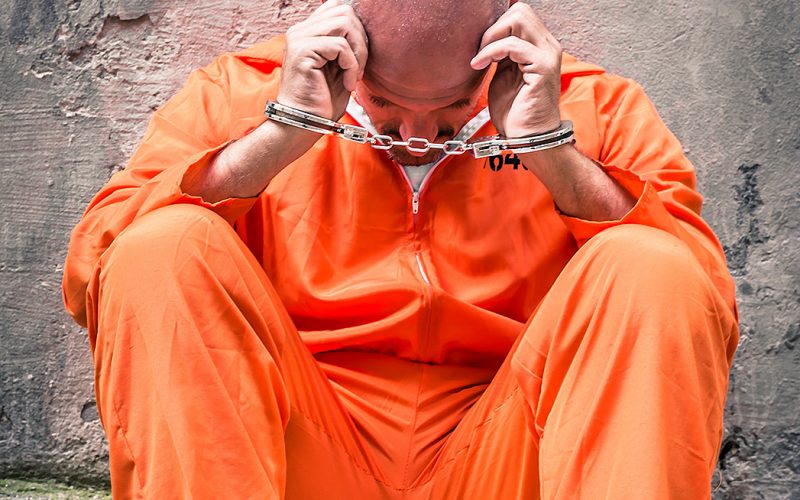

Four more innocents were released from America’s Robben Island this month. Our offshore penal colony at Guantánamo Bay still holds 158 prisoners, 84 of whom have been cleared for release. The men sent home were never charged with a crime and were cleared four years ago.

The releases may give other prisoners a reason for hope if they heard the news. During hunger strikes last spring, some of which lasted over 80 days, the military raided the prison and put 100 strikers in solitary. No one knows how or what information passes to them.

At the time, when 100 of 166 prisoners were refusing food, the ACLU, the Center for Victims of Torture, Human Rights Watch and 17 other civic groups wrote to Pentagon boss Chuck Hagel that force feeding detainees was “cruel, inhuman and degrading” — the treaty definition of torture — and called for its immediate and permanent cessation. Hagel also got a letter from Jeremy Lazarus, the president of the American Medical Association, who charged that doctors helping force-feed prisoners against their will violated “core ethical values of the medical profession.”

From February to June, the White House presided over the torturous force-feeding of at least 21 bound prisoners, a choking and gagging experience in which plastic tubes are shoved through the nostrils and down the throat while one is cinched to a restraint chair.

Cooler heads pronounce, but don’t yet prevail

In the midst of the hunger strike, a diverse group of legal scholars, constitutional lawyers and former high ranking government and military officials published a major report that said Guantánamo demonstrates “… the willingness of the United States to detain significant numbers of innocent people … and subject them to serious and prolonged privation and mistreatment, even torture.”

The nonpartisan Constitution Project’s Task Force on Detainee Treatment’s (CPTF) self-titled “most important” finding — made “without reservation” — was that “[I]t is indisputable that the United States engaged in the practice of torture,” and that “[I]t occurred in many instances and across a wide range of theaters.”

The 600-page study, two years in the making, explained “[T]his conclusion is grounded in a thorough and detailed examination of what constitutes torture in many contexts, notably historical and legal. The CPTF examined court cases…in which the United States has leveled the charge of torture against other governments. The United States may not declare a nation guilty of engaging in torture and then exempt itself from being so labeled for similar if not identical conduct.”

The CPTF declared that by authorizing torture, the government “…set aside many of the nation’s venerable values and legal principles.” I wouldn’t use such niceties as “set aside.” Government employees disobeyed, defied, denigrated and mocked the law, particularly the U.S. Torture Statute, the U.S. War Crimes Act and both the Geneva Conventions and the Convention Against Torture which are U.S. law under the Constitution. Obama himself said on April 30 that Guantánamo was “a symbol around the world for an America that flouts the rule of law.” On Sept. 24, 2009, he said, “International law is not an empty promise, and treaties must be enforced.”

Constitutional review finds high-level culpability

The CPTF’s second major conclusion was that the “highest officials bear some responsibility for allowing — and contributing to the spread of — torture.” This bombshell puts the perpetrators in legal jeopardy considering U.S. treaties governing torture. They hold that if an accused government — in this case the United States — fails to investigate and prosecute the credibly accused, other states or the International Criminal Court may be obligated to do so.

The CPTF noted that during a February 2012 visit to Guantánamo by its staff, the prison commander at the time, Rear Adm. David Woods, “was quick to point out the facility’s motto: ‘Safe, Humane, Legal, Transparent.’” And I am Marie of Romania.

Karen Greenberg, founder of the Center on National Security at Fordham University’s law school, has said of Guantánamo’s hunger strikers, “They can’t tolerate it any more. It is despair…” Ten years of indefinite imprisonment without charges, and often without mail, phone calls or access to attorneys, is so psychologically devastating that the beleaguered inmates would rather have died than drift in oblivion. In May, prisoner Al Madhwani wrote to a federal court “…Obama must be unaware of the unbelievably inhumane conditions at the Guantánamo Bay prison, for otherwise he would surely do something to stop this torture.”

Obama has ignored torture allegations made against Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Alberto Gonzales and George Bush — who did prosecutors the favor of publishing an autobiographical confession. When asked if his administration would investigate, Obama said it would be unproductive to “look backwards.” It would also be self-incriminating, since Obama himself has authorized cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment at Guantánamo.

John LaForge is a Co-director of Nukewatch, a nuclear watchdog and environmental justice group in Wisconsin, edits its quarterly newsletter, and writes for PeaceVoice.