’Tis the season for … food! The winter holidays of every sort are upon us. Did you eat a traditional family meal at Thanksgiving with grandma’s family-legacy stuffing or Auntie Mame’s made-from-scratch chocolate cream pie? Would it just not be the holidays without Uncle Joe’s famous gumbo?

If you’re like most Americans, and the holidays harbor a warm reminiscence of dishes that are lovingly created from scratch, then you are a lover of Slow Food. That’s right, Slow Food. It is the inverse of that unhealthy endowment of modern culture — fast food. And it is a movement well under way all around the world, back to the culinary delights of grandma’s kitchen.

As a writer and a food activist, I had the great good fortune this year to be chosen as a delegate to Slow Food International’s Terra Madre convention, which takes place in October once every two years in Turin, Italy. I was blessed in the love and support of my Fayetteville community with help in getting there.

It was a mind-blowing world’s fair of delicacies from every corner of the planet, revived in small select, lovingly cared-for batches made the way grandma and great-grandma and great-great-great-uncle Wojtek or Hamadi or Lorenzo used to make it.

The Slow Food Movement

But let me start at the beginning. The Slow Food movement started 26 years ago specifically in reaction to a McDonald’s being built in Rome. Europeans recognized the fast food proliferation for what it was: the insipid spread of an American blight and a threat to centuries-old cooking and eating traditions.

Italians such as Carlo Petrini, Slow Food’s founder, take great pride in the nuance and novelty of fare from each region of their country and the thoughtful concern in which the animals and vegetables are raised, the time-honored methods of food preparation.

The Slow Food Handbook, created in 1997, brings home the stunning message of loss of biodiversity in our diet:

“Over the millennia, around 10,000 species have been used for human food and agriculture, but today 90 percent of what people around the world eat comes from 120 species, while just 12 plant species and five animal species provide over 70 percent of all human food.

“It is estimated that over the last century three-quarters of genetic diversity has been lost from agricultural crops. A third of native cow, sheep and pig breeds are extinct or dying out. Similar losses of diversity have been seen in food products like bread, cured meats, cheese, wine, sweets and many others.

“Slow Food began focusing on biodiversity in 1997, particularly as it relates to:

— Edible wild species linked to cultures and traditional techniques and customs

— Domesticated and cultivated species, such as plant varieties, ecotypes, native breeds and populations

— Traditional food products.

“Many other associations and organizations are working to protect biodiversity, but generally they concentrate on wild species and pay only marginal attention to domestic diversity, selected by humans over the course of the centuries. It is very rare to find anyone concerned with food biodiversity as represented by processed food products.

“Food products are an important heritage and asset to local communities. Developed to preserve fresh foods like milk, fruits, vegetables and flowers, they are the result of wisdom passed down from generation to generation. Artisanal food processing results in distinctive products, able to express a local culture and to free producers from seasonal cycles and market fluctuations. Often it is possible to protect local ecotypes and breeds only by selling processed products.”

This passionate desire to save their culinary diversity quickly resulted in the Presidia Program, whose goal is to revive and protect the biodiversity of artisan food products, traditional methods and native crops around the world.

To that end, this year’s conference with the theme of “Good, Clean and Fair” was a kaleidoscope of panel discussions with influential international leaders of food protection. Some of the names included founder Petrini; Alice Waters, chef, author and the proprietor of the award winning Chez Panisse Restaurant in San Francisco; Pia Bucella, directorate general for the Environment, European Commission; Yanka Kazakova, European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism; and Phrang Roy, coordinator of indigneous partnership for Agrobiodiversity and Food Sovereignty.

Vandana Shiva, president of Navdanya movement and a rock star of the movement for her work in fighting Monsanto’s GMO patents on many fronts, was met with standing ovations wherever she spoke.

It was especially exciting to see the abundance of women in positions of authority from every nation, fulfilling another tenet of Slow Food’s philosophy, which promotes the education of women and girls and insists on equal respect for women’s voices.

The Terra Madre conference was paired with Salone del Gusto, a festival of vendors from more than 100 countries introducing products that had often been on the verge of extinction — fruit from the baobab tree, honey from rare mountain flowers or varieties of rice never sold commercially.

Among other things, there were jams and liqueurs, oysters, cheese wrapped in grape leaves, smoked salts, cured olives of every description, reindeer roast, fish of all kinds, apricots, alpaca ham, raisins, breads and plenty of cakes, tortes, crepes and other sweet treats.

All of these goods were raised and produced sustainably on farms and in kitchens that paid their workers a living wage and cared for the planet in every step of their production, as per the Presidia guidelines.

This conference represents changes taking place in nearly every nation, a recognition of the value of food the way it is supposed to be grown and eaten, for our health and for the health of the planet.

These same ethics are at the core of a burgeoning movement right here in Fayetteville at our Farmers’ Market, our Community Supported Agriculture farms, our many restaurants beginning to emphasize locally grown vegetables and meat in their menus and a growing group of dedicated volunteers throughout our city working to make “good, clean and fair” food available to everyone, starting with our very own local Slow Food chapter Ozark Slow Food.

Great-grandma would approve.

Quinn Montana is the author of the book “Worship Your Food,” a guide to becoming free from the oppression of chemical agriculture and save money doing it. She is also an organic gardener and a local food activist. Ozark Slow Food welcomes new members. Information can be found at ozarkslowfood.org or facebook.com/pages/Ozark-Slow-Food/115590439259.

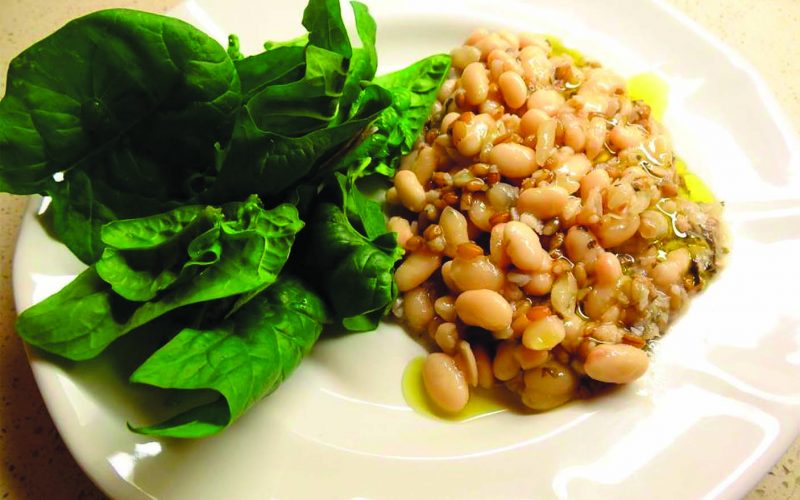

Simple, Amazing White Beans

Simple, Amazing White Beans

Always look for locally grown and chemical-free!

Need:

A crockpot

1 c. dried cannellini beans

Dried rosemary

2 cloves garlic

Olive oil

Salt

Small piece of kombu (Japanese seaweed)(optional)

Filtered water

Place your beans in 3 cups of water in a quart jar before you go to bed. In the morning drain the water, pour beans into crockpot, add 2 c. fresh water and 1 tsp. fresh crumbled rosemary leaves. Adding a strip of flavorless kombu helps to soften the beans as well as aid in digestibility. Set crockpot on low.

When you are ready to eat an evening meal, the beans will be cooked!

Serve over brown rice with steamed veggies. Try squares of celery root, carrot, kale, spinach or all of the above! Also, try substituting brown rice with buckwheat kasha or cooked rye berries. Saute minced garlic in 3 healthy Tbs. of olive oil and pour over everything. Salt to taste.

Celeriac (celery root)

Need:

1 celery root

2 white or yellow onions

1/4 c. olive oil

2 cloves garlic or more

Salt

You’ve seen those really cool looking melon-sized root-thingys at the local co-op and they look like fun, but what do you do with them? Here’s one idea. Choose one that is heavy, making sure it isn’t spongy or beginning to look a little pruney. Its texture should be somewhat like a fresh parsnip or carrot.

Quinn Montana and Vandana Shiva — president of Navdanya movement that is fighting Monsanto’s GMO patents in India — at the Terra Madre convention in Turin, Italy.

You have a knife sharpener and you always keep your knives sharp, right? OK. Cut off the outside of the celery root and freeze it for soup stock. Now cut what’s left into 1-inch squares. Peel your onion and cut that into roughly 1-inch squares as well. Steam together in a pot until just barely soft. Place all in a square baking pan.

Saute garlic on low heat in 1/4 c. olive oil; do not let it brown. Pour over celeriac and onions, toss with fork and gently salt. Bake on top shelf of oven preheated to 400 degrees until top is beginning to brown, about 15 minutes. Goes great with chicken, turkey, lamb or pork. Can also be a tasty side with cornbread stuffed squash or other dishes for a great vegetarian meal.

— From Quinn’s Kitchen