JOCELYN MURPHY

jmurphy@nwadg.com

Picture a flagpole in your mind. What does that tall metal pillar mean to you? A flagpole can serve as a spot for meeting or gathering; it can be a landmark; it can be a piece of the past. It almost always bears some sort of symbol: a flag representing community, religion, country.

At the Bentonville contemporary arts space the Momentary, the old flagpole from the building’s factory days presented a unique opportunity to raise new voices and new perspectives on the campus, literally. In the spirit of adaptive reuse architecture at the Momentary, artists have been invited to create their own flags to fly from the historic pole — sharing their own explorations on the symbolism of such a piece of fabric.

“How do we allow artists to claim space and tell stories on our campus?” Kaitlin Maestas, assistant curator, shares one of the prompts that ultimately led to the project. “We wanted to open up the conversation and allow artists to create the flag that we hung, rather than a traditional American flag.”

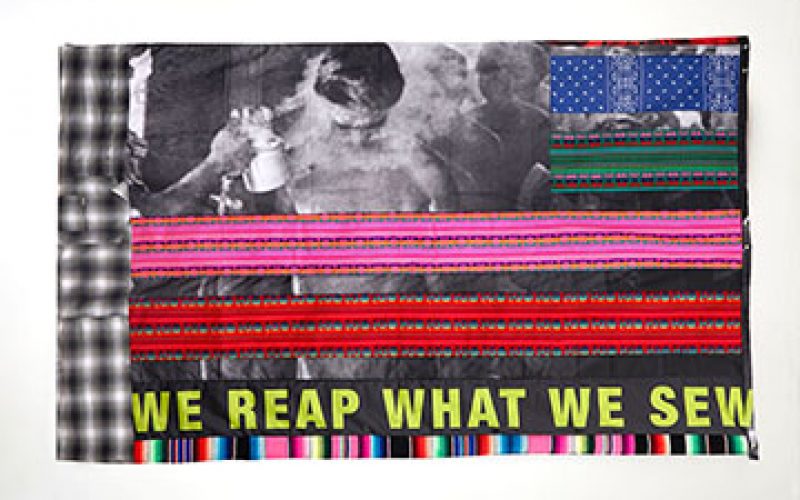

The premiere flag for the Momentary Flag Project, created by Christopher Myers, was on display from June 24 through Oct. 6. The following day, a flag created by multidisciplinary Los Angeles-based artist Gabriella Sanchez took its place and will fly from the pole until Jan. 10. Sanchez took a few moments with What’s Up! to dig a little deeper into her design, “WE REAP WHAT WE SEW.”

Los Angeles-based artist Gabriella Sanchez submitted an original design for the Momentary Flag Project titled “WE REAP WHAT WE SEW (Past and Present Patterns).” Here, the back side of the flag displays its title sewn among found fabrics and positioned beneath an image referencing the Bath Riots in 1917, when laborers coming across the Mexico-U.S. border were required to strip and be fumigated with toxic chemicals such as gasoline, pesticides and Zyklon B.

(Courtesy Photo/Gabriella Sanchez)

Q. What can you share of the process that brought you to the finished flag incorporating so many emotional layers, but also the physical layers — fabric that is immediately identifiable as clothing, worn; vibrant colors contrasted with black and white photos; and text.

A. For this project I wanted to approach it in a similar mentality I use with my paintings. I often use touch points from personal story and history through archival family photographs. For this project, though, I wanted to use images that had a broader context since this would be exhibited outside of L.A. and would function as a flag in an outdoor public space. I also still wanted this project to have a personal connection, so that’s where the fabrics came in. I decided to look at textiles, patterns and fabrics that had personal and familial connections but could also function in a certain wider context as well. That’s where the idea came from to mix shadow plaid flannel shirts, bandannas and woven fabrics from Mexico that I bought downtown near my L.A. studio.

Q. The flag series “asks artists to consider how flags shape our understanding of place and identity.” The Momentary itself has also done that, in a way, with its use of “adaptive reuse architecture” and integration of the region’s and the building’s history in establishing a new relationship with the community. Was any of this on your mind as you designed your flag?

A. That’s a good question and in short, yes, it did shape the way I approached the project. I was immediately interested in creating a flag itself — not just a painting or digital composition to be used as a surface design for a flag, but to create an actual flag. Though to do that, I also had to examine the heavy colonial and imperial history associated with flags. I wanted to complicate, reconstruct and unravel the idea of a flag. To do this, I considered what textiles, fabrics, colors, motifs and patterns I would want to use in order to attempt to distill the way in which myself and my family have experienced and developed relationships with our community, our city, our country and the land that has been denied to us and the land we occupy.

Q. What do you think it is about the idea of a flag that ties it so closely to identity for so many? And how does an artistic flag fit into, or maybe dispute, that type of narrative?

A. Flags have historically been most commonly used in our history as a form of conquest, a form of distorted pride, a form of ideological implantation in the mentality of the individual. And because of that history, it creates an opportunity of transformation and a form of resistance when people from marginalized communities use the idea of a flag as an opportunity to assert their own vision of their own humanity and experience.

Q. How do the two sides of the flag relate to each other? Are their messages and meanings in conversation, expounding on each other, or are they disparate?

A. Usually a flag is one sided; even though it’s a three-dimensional object, it only shows you one (usually digitally produced) image. However, this flag was stitched together from disparate textiles with varying patterns of significance. These images were sewn alongside digitally produced images of archival historical images that represent moments in which Latinx communities resisted, and these powerful images exist because of those real life actions and events.

For me, one side of the flag represents and respects endurance for survival and the other side represents and respects the growth of hope and will that moves towards a life beyond enduring.

FAQ

The Momentary

WHEN — Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday 10 a.m.-7 p.m.; Thursday-Saturday 10 a.m.-10 p.m.; closed Monday

WHERE — 507 S.E. E St. in Bentonville

COST — Free

INFO — 367-7500, themomentary.org

FYI — Sanchez’s flag will be on display through Jan. 10.