Northwest Arkansans honored in three categories

BECCA MARTIN-BROWN

bmartin@nwadg.com

The 2021 Governor’s Arts Award is not the first one for lifetime achievement Trout Fishing in America has received. And Northwest Arkansas musicians Keith Grimwood and Ezra Idlet hope it’s not the last.

“They tried to make us stop twice before, but we just kept going,” Grimwood jokes of lifetime achievement awards. “I don’t know quite what ‘lifetime achievement’ means. It is nice to be recognized. I feel honored by the whole thing. You can do what you do and just be invisible, but it’s nice to have somebody point it out.”

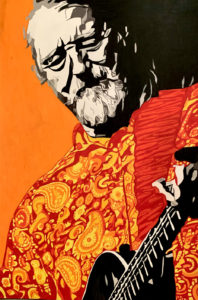

These portraits of Keith Grimwood (left) and Ezra Idlet, the duo that has been playing music as Trout Fishing in America for most of 45 years, were created by Idlet’s sister, Susan Idlet, whom he calls “a very talented artist.” TFIA was presented with the 2021 Governor’s Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement.

(Courtesy Images/Susan Idlet @susanidletart on Instagram and Facebook)

The awards, issued annually by the Arkansas Arts Council, “recognize Arkansans who have made significant contributions to maintaining, growing and enhancing the arts in our state,” according to Stacy Hurst, secretary of the Arkansas Department of Parks, Heritage and Tourism. “These artists and art supporters are part of the cultural heritage of Arkansas and are fundamental components of our creative economy and quality of life.”

Idlet and Grimwood, who have been playing music together for 42-35 years — depending on how you do the math — were nominated by Delynne West, a music specialist at Springhill Elementary in Bryant.

“When I found out about the awards, they were the first people to cross my mind for lifetime achievement,” she says. “They have impacted families over the world with their music because it appeals to all ages.

“From my perspective as a teacher and a musician, they truly support others to find their creative outlet, whether through songwriting, singing and dancing during a concert, or working with artists in their studio,” West says. “I can’t imagine there are two more generous entertainers in the industry.”

West says she was introduced to Trout’s music in the early 1990s — about the time they moved their families to Northwest Arkansas from Houston — and met them after a concert at Little Rock’s Riverfest in 1998 or 1999.

“At that Riverfest concert, they mentioned how one of their songs had been written by children in a songwriting workshop,” she remembers. “Afterwards I asked how I could get the ball rolling to have them come to my school. They gave me contact information, and it took me a few years to gain funding. In 2004 I was finally able to make it happen through a grant from an anonymous donor. Since then I have applied for several grants to keep the songwriting workshops going, as well as securing funding through my school PTO and a wonderfully supportive principal.

Joe Doster of Huntsville, recipient of the 2021 Governor’s Arts Awards Folklife Award, demonstrates how to carve a wooden spoon with hand tools at the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale. Doster is also a blacksmith and was recently featured in a Shiloh Museum video available on the museum’s YouTube channel.

(File Photo/Ben Goff)

“One of the reasons I have been able to receive grants is due to the cross-curricular aspect of the workshop,” West goes on. “I realized that first year that they weren’t only helping my students find their voices through music, but words as well. They encourage songwriting participants to write about what they know and use descriptive words to convey their message. During the workshops we generally finish a verse or two and the chorus. In the following lessons we finish up the story and talk about what kind of musical form would best suit the story. We record the vocals as a class and end up with a finished product. I love how the students will discuss the creative process, and they really feel like they own their work when it’s complete.”

Idlet and Grimwood both love seeing something started in a kids’ workshop grow up to be a full-fledged song — as is “Alien In My Nose” in their regular catalog. But kids were not their first audience. Grimwood was a classically trained bassist with the Houston Symphony, and Idlet was a garage-band rocker when they started playing together in a group called St. Elmo’s Fire. That evolved into Trout Fishing in America on an extended visit to California, where they made their musical living on street corners and named their duo based on the Richard Brautigan novel.

It was having children that led to children’s music — and now it’s grandchildren and aging and current events, like the covid-19 pandemic. Grimwood and Idlet were performing in Pennsylvania in March 2020, “and we were concerned about covid at that point,” Idlet says. “We got to the venue, and everybody wanted to hug us, shake our hands, take pictures with us. At that point, we were polite. But we came home and went directly into quarantine. Then jobs started rescheduling. And we let a few go on purpose — we didn’t want to catch it, and we didn’t want to be responsible for bringing people together to catch it!”

“That was March 7, our last live show,” adds Grimwood. “I look at the calendar of what we have missed since then — for one, we released an album with Wheatfield; the entire release tour was canceled. We released an album with Michael Cockram and Susan Shore; the entire release tour was canceled. We had festivals lined up all over the country. But that is all on the business side. I’m enjoying being home — I’ve been been on the road for 40-something years. The deal is not just waiting for it to pass. It’s embracing life as we know it right now.”

Bob Bogle and the late Marilyn Bogle (pictured) and their family received the Patron Award as “generous supporters of the arts in Northwest Arkansas,” having “donated to improvements in the arts, history, healthcare, athletics, academic and cultural spheres and have helped perpetuate and grow the arts statewide.”

(File Photo)

“It’s like when a lizard loses its tail; it’s growing back different,” says Idlet. “I love live shows, but finding that satisfaction in the writing and the recording has been really wonderful. While we are touring, the time to develop ideas is severely truncated. Now we come together, we write, we listen, we edit. We have time to go out on creative limbs and to make those limbs stronger by examining and reexamining them.”

They’ve also found a unique niche for releasing their music, something they’re calling “Tackle Boxes.” With each release, fans get a download of three songs, a video of Trout playing those songs, a little bit of background on each song and artwork by Susan Idlet, Ezra’s sister and a well-known Northwest Arkansas artist. With that, and the occasional livestream, life for Trout Fishing in America is going swimmingly as they prove lifetime achievement doesn’t equal retirement — at least, not this time!

Joe Doster

Huntsville

Folklife Award

In a video created by the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, Joe Doster is working in his blacksmith shop. He’s dressed in a blue denim shirt, jeans and suspenders, and he sounds a lot like folk music icon Arlo Guthrie, describing not the Thanksgiving tale of “Alice’s Restaurant” but instead how he starts his fires with wood chips from his wood shop and prefers to “make do” with recycled materials because “I think it’s in the spirit of the Ozarks.”

However, Doster received the Folklife Award for his wooden creations, which range from cutting boards to intricate period furniture. He has long been a member of the Arkansas Craft Guild, is founding president of the board of the Arkansas Craft School, taught for many years in the public schools and is now mentoring his son to take over the family business. He credits his father as where he got “most of my figure-out-how-to-do-it-ness.”

“Many of our parents that didn’t have a lot knew how to do stuff,” he says. “That was back in a time that when things broke, you could fix them.”

Both Doster’s parents were from rural Arkansas, so they returned to Arkansas upon his dad’s retirement. Doster graduated from Little Rock Central High School in 1972 and went off to study history and political science at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Disenchanted by the politics of the day, he was going to drop out of school, but his roommate encouraged him to stay one more semester and take a woodshop class. “I absolutely loved it,” he remembers, and transferred the next semester to the University of Central Arkansas in Conway, which had a “wonderful” industrial arts program.

Doster learned it all — hand and power tools, old-fashioned print making, drafting. Then he did drop out and went to live in a cabin in the woods for a year with his dog, lacking just four hours for his bachelor’s degree. “It was a great thing to build your inner confidence,” he says now. And he met his future wife, who was living in a tent on the property at the same time.

Doster turned his knowledge into a paycheck by joining a friend’s woodworking business, making cutting boards and butcher blocks. They traveled the juried art show circuit for more than a decade — “not an ideal lifestyle unless you love the road,” he says. Ready to stay home, he landed a job with the park service at the Buffalo National River, where he made pioneer woodworking part of his interpretive programming.

“It was the greatest way to attract kids,” he says, recalling them “piling out of the station wagons.” “And I fell in love with teaching again.

These portraits of Keith Grimwood (left) and Ezra Idlet, the duo that has been playing music as Trout Fishing in America for most of 45 years, were created by Idlet’s sister, Susan Idlet, whom he calls “a very talented artist.” TFIA was presented with the 2021 Governor’s Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement.

(Courtesy Images/Susan Idlet @susanidletart on Instagram and Facebook)

“I did that for three summer seasons,” he recounts. “It was probably the first experience I’d had working with a majority of folks that had advanced degrees — very, very intelligent people doing pretty hard work. That was inspiring, to be around folks that were pretty sharp.”

Over the years that he taught in public schools, Doster always kept his creations on the market through the Arkansas Craft Guild shops and got involved with the Arkansas Craft School in Mountain View “trying to keep what we do alive.”

“It’s important — my friend Doug Stowe [from Eureka Springs] refers to it as the wisdom of the hand — and I like that phrase,” he says. “There’s something inherent about the connection when we create with our hands in concert with our heart and our mind and our eye, that is innately human. And keeping that going is really important for humanity.”

That’s Doster’s hope for any publicity surrounding the Governor’s Arts Award.

“I hope it triggers a ‘want to know,’” he says. “I want to get people involved in it. The other thing is to at least have a full appreciation for it or begin to, so when they see a product for sale, they don’t look at the price and set it down.

“The award is a great honor. But it’s also a representative award. I’m one of a great many creative people I know.”

Bob Bogle Family

Bentonville

Patron Award

The award praises Bob and Marilyn Bogle and their family as “generous supporters of the arts in Northwest Arkansas,” having “donated to improvements in the arts, history, healthcare, athletics, academic and cultural spheres and have helped perpetuate and grow the arts statewide.”

Marilyn Bogle died on Jan. 23, 202o, and Bob Bogle doesn’t sit for interviews. Their son, David, is the founder of the Museum of Native American History in Bentonville. Their daughter, Becky Alexander, shared these thoughts about her parents and the award.

“My parents moved to Bentonville in 1951, one year after their marriage, and immediately fell in love with the small town,” she begins. “Both can be described as warm, caring, kind and generous. Once you met them you were their friend for life.

“Dad still lives in the house they built in 1955 just a few blocks from downtown. Growing up here was typical for small-town life: Dad managed the Walton 5-10 and later the Walton Family Center, while mom was busy with kids and everything that involves. Over the years they watched Bentonville grow from the small town where you knew everyone to the busy city it is now.

“After Dad retired from Walmart in 1982, they began traveling extensively, always visiting beautiful gardens, museums and historic locations,” Alexander continues. “In the late 1980s, Mom started traveling to New York City in December to see the decorations and go to Broadway plays. Shortly after, the Walton Arts Center was built in Fayetteville, which now brought Broadway to our area. Each year Mom and Dad chose to sponsor the Christmas themed Broadway play that would be performed during the holidays. Later they continued that tradition with SoNA by sponsoring the Christmas performance. Dad was never the one to attend performances, but Mom would grab a friend or family member and off she would go.

“Neither can be described as particularly artistic or musical, yet I think both were in their own way,” Alexander muses. “Dad had a passion for gardening and would bring ideas he saw while traveling back to his garden, and mom had her ‘aha’ moments. If you got a phone call that started with ‘I just had an idea,’ you knew you were about to be recruited for something. She always loved entertaining and decorating for holidays. Having family and friends around is what made her happiest.

“They recognized how important the arts were to the community and how much it enriches the lives of everyone and how necessary it is to support them,” Alexander says. “They have always felt very blessed in their lives and fortunate to be able to assist other organizations in any way possible. All of us in the family have our interests in the arts too. David opened the Museum of Native American History, and Bob and I are art collectors of American folk art and Native American art. We all love to attend a great performance of a play or listen to a wonderful concert.

“It is an honor for our family to be given the Governor’s Arts Award. Now more than ever we can be grateful for the arts and the efforts they have made this past year to bring virtual tours and performances to our home. It reminds us how much we appreciate the arts and what we would miss without them and how much they rely on our continued support now and in the future.”

Other Winners

Arts Community Development Award — Pat Qualls-Taylor of Jonesboro, a retired high school choir director and private music teacher who was elected to the Arkansas Music Educators Hall of Fame in 2001.

Arts in Education Award — Kai Coggin of Hot Springs, a widely published poet and a teaching artist in poetry with the Arkansas Arts Council and Arkansas Learning Through The Arts.

Corporate Sponsorship of the Arts Award — Bylites Inc. of Little Rock, an event rental and production company.

Individual Artist Award — Warren Criswell of Benton, a painter, printmaker, sculptor and animator who has had 41 solo exhibitions in the United States and one in Taiwan.

Judges Recognition Award — Elmer Beard of Hot Springs, a poet, author, retired educator and community activist whose love of service and uplifting the African-American experience has led to a lifetime of community and civic leadership.