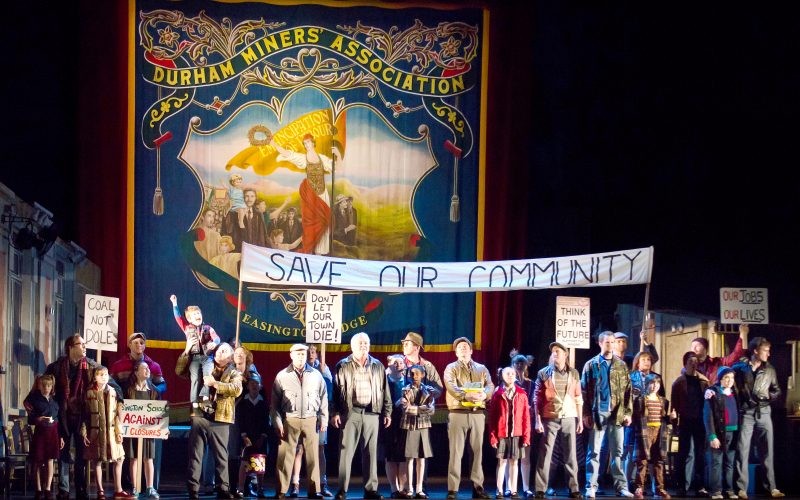

Billy Elliot the Musical plays out amid the turmoil of the 1984 coal miners’ strike in Northern England, one of the darkest times in modern British history. As young Billy studies ballet, the mining town where he lives experiences relentless hardship and despair.

Director Stephen Daldry, book writer and lyricist Lee Hall, composer Elton John, and choreographer Peter Darling deftly interweave the story of the miners’ struggles with Billy’s journey, which becomes a beacon of hope in a dying community.

“It’s not possible to exaggerate how close Britain came to civil war,” Daldry said. “That strike was one of the most important events in my life, as well as in domestic village politics. It bookends the show.”

In 1984, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), with 250,000 members, was among the most powerful unions in Britain. The coal industry had been nationalized in 1947; in essence, it was owned by the country.

“The profits and the use of that resource were commonly held, just like a library or school,” Hall said.

A general election was held: Conservative (or Tory) party were voted out, and the Labour Party was voted in. The NUM flourished.

In the aftermath of the Conservatives’ defeat, Nicholas Ridley, a right-wing member of parliament, drew up a plan advising the Tories how to conquer and dismantle the coal industry the next time their party took power. The Ridley Report included a suggestion that the country “train and equip a large, mobile squad of police, ready to employ riot tactics in order to uphold the law against violent picketing.” His ideas were supported by Margaret Thatcher, who became prime minister in 1979.

“Her ideology and economic outlook was based on letting big business look after public needs.”

After winning re-election in 1983, Thatcher implemented Ridley’s plan. Coal from abroad was stockpiled, and many power stations were switched over to oil. The National Coal Board announced that 20 mines would be closed. A national strike was declared in March, 1984.

The show gleefully and savagely vilifies former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, architect of a policy to destroy the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

“It became confrontational very quickly,” Hall said. “Thatcher sent a lot of London police up north. From the start they were far too aggressive. When things got violent, it became a common occurrence for the police to arrest ‘troublemakers’ in their houses.

The streets would be flooded with policemen who would break down doors, and bring out ringleaders of the union who had supposedly committed violence on the picket line. Sure there was violence by the pickets. But there was also violence by the police. It escalated, and there were pit battles, including a very famous one called Orgreave. The police, on horses, with their riot shields, attacked and beat up many miners.”

After a year, the resources of the state were infinite, and the miners were broke. Very gradually, people started to drift back to work. It became quite clear that the strike was going to be broken, and Thatcher had won.”

At the end of Billy Elliot, it’s clear that the mining community is on a path to nowhere. But Billy is poised to go in a different direction. His talent and passion lift the spirits, as he heads down a road filled with infinite possibilities.

Visit us on www.facebook.com/freekly for a chance to win two tickets to see Billy Elliott on opening night, Nov. 4, at the Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville. Don’t have Facebook? Text (479-387-8794) or email (tbaker@nwaonline.com) your name and contact information for your chance to win.