JOCELYN MURPHY

jmurphy@nwadg.com

By its simplest definition, “folk music” is just music for folks. It’s music that tells the stories of people’s lives, says Ozark Folk Festival organizer Nancy Paddock.

“It’s the music that starts in the living room and the front yard,” she muses, noting that the genre, if that’s even still the most applicable word, “has got a fuller voice now than it’s probably ever had. It’s not as regional as it used to be, but I think it touches more of a common theme across the spectrum of folk music.”

The Ozark Folk Festival’s 74th incarnation, descending on Eureka Springs Nov. 11-14, reflects that breadth of diversity with a lineup of artists that are both established and up-and-coming, local musicians steeped in Ozark culture and national names influenced by other regions of the country, and music that encompasses country, bluegrass, jazz, pop and even hip-hop and MCs.

“The festival started with the idea of preserving the traditional Ozark music and dance,” Paddock shares. “They were trying to preserve what was happening 30 years ago. Now we look [back], we’re in the 1970s. So if we’re trying to preserve the traditions, we have more decades of music to preserve, which makes the whole spectrum of folk music so much larger.”

“‘Folk’ is a word that means different things to different people, which works for us because it allows us to be broad and inclusive,” adds Dan “Danjo” Whitener, banjo player/vocalist with festival headliner Gangstagrass. “It means that each of us can add our own folk music to the mix, and it’s all good. None of it is wrong.”

“It may be hard to define,” piggybacks his bandmate Rench (producer/guitarist/singer/beatmaker/creator), “but there is a way that music can come from the patronage of those with resources and serve the preferences of an elite, or come from the desires of people without resources to share and create together. What is a music that is played by folks for folks, growing out of that desire to sing and play together? I suppose many kinds of music came from that, and that’s why ‘folk’ can be a really broad term. At the end of the day, I just know I like folks, so when they are making stuff from the heart, it is great.”

“This is organic, and it comes from the heart,” chimes in MC/singer Dolio the Sleuth. “We can do it live, on command, in whatever space we’re in, and we don’t need anything besides ourselves, and some folks to experience it.”

Gangstagrass is an Emmy Award-nominated multiracial five-piece that explores the common ground of bluegrass, American roots music and hip-hop as a folk music — blending America’s rural and urban music traditions.

“Where to start?” Danjo begins when considering the overlap between the bluegrass and hip-hop communities. “The structure of the music itself, improvisation with traded breaks; the folk storytelling lyrical content; the cultural and class similarity of the performers and listeners; the relative young age of both 20th-century genres. Even the way that the genres were created, through modern-day synthesis augmented with state-of-the-art technology.”

“You can see both kinds of music as essentially a folk tradition, birthed out of shared struggles and methods of making music communally without resources,” Rench adds. He points to the exploitative history of the Appalachian region, and the exploitation of cities’ labor markets that concentrated poverty in places like the Bronx in the 1970s, as unique examples having many commonalities.

“The way people create and bond, build trust in their communities, share vocabularies and stories of struggle and rebellion — you will find that down underneath it all,” Rench goes on. “The music expresses those things because it was born in each case by the way people without resources could get together and create a shared music and improvise a musical conversation out of the tools they have.”

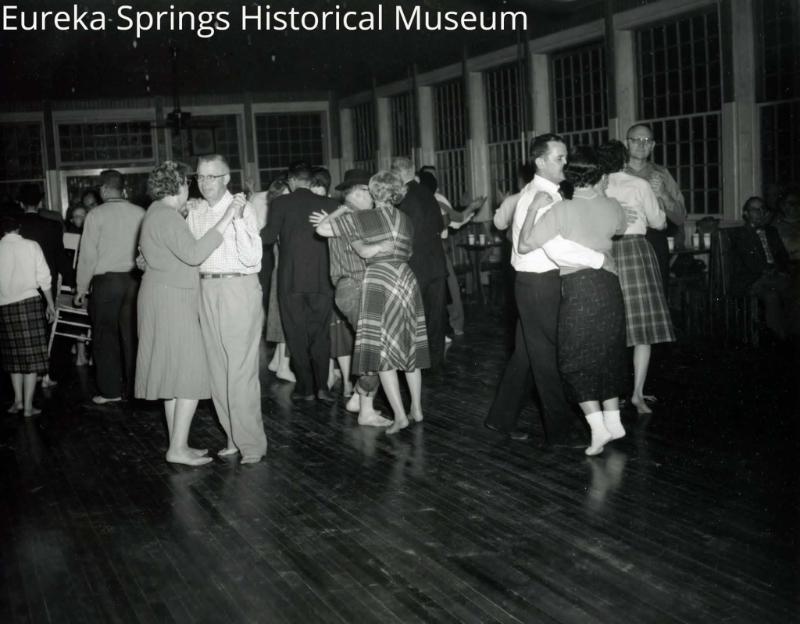

Gangstagrass’ headlining show will be on Nov. 13 at The Aud, but music will be rocking all weekend at The Aud, Main Stage, the Basin Park Bandshell and at the Basin Park Hotel for the legendary Barefoot Ball. “A selection of some of the best local musicians in the area” will be highlighted with free shows at the park, Paddock shares, and each day will begin with two local singer/songwriters as another way to spotlight local performers. Many of the national acts performing in the evenings are faces Eureka Springs and Northwest Arkansas will remember from previous visits.

Though the region and Eureka Springs itself continue to change, Paddock asserts that between the Eureka Springs Historical Museum and events like the Folk Festival supporting local artists, “we are preserving the music that is still developing in our mountains and rivers and streams.”

“For decades, it was a town celebrating its heritage,” she says of the festival’s origins. “But now it’s a town presenting its heritage. So it’s changed from being something that is a town festival to something that’s a town presenting a festival.”

__

FAQ

74th annual Ozark Folk Festival

WHEN — Nov. 11-14

WHERE — Multiple venues in downtown Eureka Springs

COST — Performances vary; some free

INFO — 253-7333, facebook.com/OriginalOzarkFolkFestival

FYI — Proof of full covid-19 vaccination or negative test within 72 hours will be required for some shows; temperatures will be checked at the door for some performances; masks will be required indoors. Visit website for full information.

__

FYI

Ozark Folk Festival

Schedule

Nov. 11

7 p.m. — Todd Snider, with opener Chucky Waggs, and Bear and Sofia, at The Aud. $40.

9 p.m. — Barefoot Ball, with Arkansauce, at Basin Park Hotel. $15.

Nov. 12

6 p.m. — Hedghoppers

8 p.m. — Jonathan Byrd and the Pickup Cowboys, with Melissa Carper and the Blue Hankies on at 7 p.m., all at The Aud. By donation of cash or non-perishable food items, benefiting the local food bank and People Helping People.

Nov. 13

8 p.m. — Still on the Hill, with Mighty Fine Time, on at 7 p.m., at Main Stage. $10.

7 p.m. — Gangstagrass, with opener The Creek Rocks, at The Aud. $29.

Nov. 14

7 p.m. — Sam Baker, with Tim Lorsh, at Main Stage. $20.

Basin Springs Park

Sixteen local musicians and singer-songwriters will perform at the Bandshell from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Nov. 12-13 and from noon to 4 p.m. Nov. 14.