A Different Kind Of Folklore: Oral history project considers drag community in Arkansas

Arkansas Folk and Traditional Arts’ new project, an oral history of the Arkansas drag community, promises to uncover some fascinating accounts of the evolution of the art form in the Natural State, says the organization’s coordinator, Virginia Siegel.

“As a relative newcomer, I was pretty blown away at how Arkansas has actually been a pretty key player in the history of drag,” she says. “I think that’s such a cool story that a lot of people don’t know. The drag pageant circuits really started because of Arkansans, and a lot of winners have been Arkansans. [Our goal is] making sure that that story is preserved and shared.”

“Arkansas has a rich drag history that dates back at least to the 1930s,” says Joseph Porter, Northwest Arkansas Equality CEO and board president. “Celebrity drag queen Harvey Lee toured the nation performing in clubs from the 1930s until the ’80s, but called Arkansas home. Drag was part of mainstream charitable fundraisers in rural towns, a source of comedy on military bases, and entertainment in the Japanese internment camps in the 1940s. While these drag shows weren’t LGBTQ events, they opened doors for rural Arkansans to explore gender fluidity and social norms.”

In the 1970s, says Porter, Arkansas was the epicenter of the gay pageant circuit.

“The 1970s brought Miss Gay America to Arkansas through the pageant’s first winner, Norman Jones/Norma Kristie,” he says. The pageant’s operations were based out of Arkansas for 35 years and often held in Little Rock’s Robinson Theater. Partially because of Jones’ efforts and the national pageant’s location, Arkansas’ drag scene flourished as contestants competed in city preliminaries to Miss Gay Arkansas and ultimately vied with more than 50 entertainers from across the country to become Miss Gay America. For over 50 years, these very visible displays of pageants, drag shows and nightlife helped create queer spaces, acceptance and a supportive community for Arkansas’ LGBTQ people, Porter says.

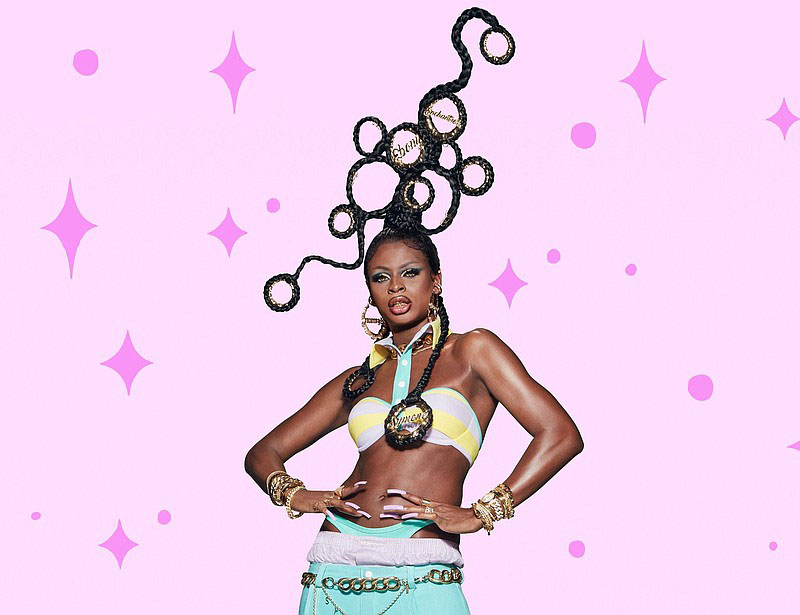

This past year, the Arkansas drag scene made news again when Conway’s Symone (the drag name of Reggie Gavin), was crowned the winner of Season 13’s “RuPaul’s Drag Race” in 2021. And the Miss Gay America Pageant will be held in Little Rock in January 2022.

Siegel is a professional folklorist who moved to Arkansas from Kentucky, where she served as the folklife specialist for the Kentucky Folklife Program. While there, she worked on a project about drag performers that she found fascinating.

“I’m always interested in projects that widen people’s understanding of what tradition is and what folklore is in our lives,” she notes.

When collaborator Deena Owens, a University of Arkansas Mullins Library employee who has history as a dresser for performers on the drag circuit, brought up her background, the two linked their areas of interest and experience to launch the project because, as Siegel notes, “it’s important to document the diversity in our communities. Drag is actually a pretty classic example of folklore, if you think about it, because it’s an amazing artform that is definitely learned peer to peer. In drag, you have drag families with drag mothers and daughters, and that’s really a classic form of apprenticeship that’s just using different words.”

For now, the organization is asking those who might want to help document the history of the drag community — performers, costume designers, venue owners, audiences — to fill out a brief online form to indicate interest. Owens and Siegel will follow up when the interviewing process begins, and Porter says his organization will also be a collaborator.

“Northwest Arkansas Equality is excited to be part of the university’s Arkansas Drag Community Oral History Project, and also maintains a collection of local LGBTQ history and memorabilia,” Porter says. “We hope to connect the library’s researchers with a variety of artists and provide context to this history of what is essentially ‘queer theater.’”

“With oral history, what we’re interested in is creating an environment where we ask really open-ended questions,” Siegel explains. “The interview is led by the interviewee, so they can sort of take control of the interview and share what they think is most important to them — an oral history provides that space. At Arkansas Folk and Traditional Art, we use trauma-informed oral history [tactics], as well, especially with communities that have experienced hate crimes and prejudice. It’s important to have a space where we can put that control into the hands of the interviewee, so they can avoid topics that are trauma inducing, so all of our skilled workers are trained in basic trauma-informed approaches.

“We’ve also been having a lot of really important, really timely conversations about post-custodial collecting — ‘How do you collect in a way that isn’t sort of taking someone’s story and owning it in a sort of very patriarchal, top-down system?’ We’re interested in trying to combat that and find ways of sort of sharing ownership with the community. This kind of project really helps us work through some of those details: ‘How do we provide a service to the drag community in a way that we’re not taking ownership of the narrative, but helping to support and preserve that?’”

Siegel says she hopes that there will be a chance for the public at large to see AFTA’s work on the subject within a year or two.

FYI

Arkansas Drag Community Oral History Project

Those interested in participating in the oral history project can visit folklife.uark.edu/drag/ to fill out a brief form.