Rogers Historical Museum sets the table with 100 years of glassware

BECCA MARTIN-BROWN

bmartin@nwaonline.com

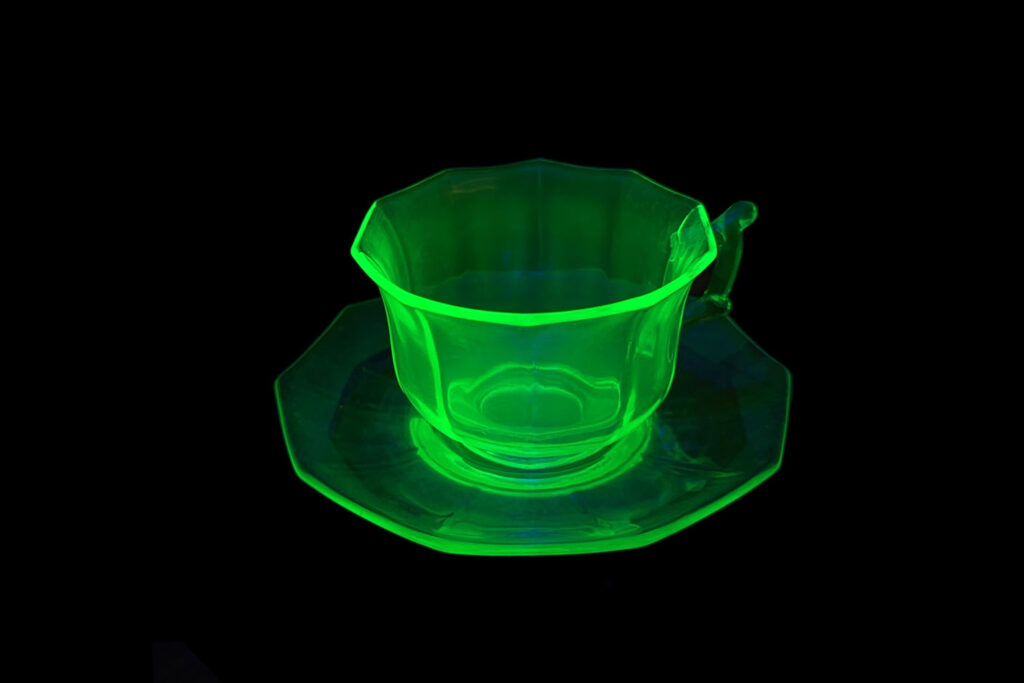

Pieces of it sparkle like diamonds, and others magically glow under black light. But cut glass, uranium glass and other decorative glassware — although often displayed in a china cabinet — were also part of day-to-day life at the turn of the 20th century.

“Fancy glassware — especially cut and pressed glass — was often considered a traditional wedding present,” says Serena Barnett, director of the Rogers Historical Museum and curator of the “A Century of American Glassware” exhibit. “Not only would the newlywed couple need everyday glassware, such as bowls, dishes, pitchers, condiment bottles, and such, it was a social expectation to own a selection of finer glassware.

“A candlelit room with a table set with sparkling glassware served as an impressive centerpiece for special occasions — bridal showers, weddings or funerals — or during holidays [like] Easter, Thanksgiving and Christmas,” she adds. “Decorative glassware has graced American homes and tables for centuries.”

Everything in “A Century of American Glassware,” which opened Feb. 17 and remains on show through Aug. 10, is from the museum’s permanent collection, Barnett says.

“For this reason, the exhibit’s focus is determined by the parameters of what we have in the collection,” she explains. “Examples of different types of glassware ranging from the 1870s through the 1970s will be highlighted and include brilliant cut glass, engraved glass, pressed glass, Depression glass, uranium glass, and mid-20th century glass.”

The first American glass factories were established by European immigrants who came from glassmaking traditions, Barnett begins the history lesson.

“Germany, Italy, and the British Isles all had highly developed glass industries, and early American glassware often closely followed European styles,” she says. “The development of the first commercial glass pressing machine in 1825 was a revolutionary moment for the American glass industry. The pressing machine allowed glass to be mass-produced by pressing molten glass into a mold, whether plain or engraved, creating an entire piece in a few seconds.”

The Victorian culture greatly influenced social sensibilities throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, Barnett adds.

“Since fancy, decorative glassware is the epitome of fine domestic art, it would often be on display in a china cabinet in the dining room when not in use,” she explains. “Delicately etched, colored glass, and fine crystal glasses with stems were the most sought after, especially for table place settings. Fine china dishes with hand-painted decorations were particularly appreciated, especially when large collections included all the special matching accessories such as creamers, butter plates, cups, saucers, side dishes, salad plates, etc.”

Uranium glass, which glows under ultraviolet light, dates back to the early 19th century, Barnett says, when “European glassmakers used uranium as a colorant to achieve a distinctive yellow or green hue.”

“When pressed glass became popular later in the century, American factories began using uranium, which lasted until the 1930s,” she says. Then, “in the 1940s, the use of uranium was restricted to military purposes during World War II and throughout the Cold War era into the 1990s.” Highly collectible today, uranium glass is displayed, not used, due to the radioactive effects of uranium. Don’t worry, Barnett hastens to add. It’s no more dangerous than the radiation levels of a microwave oven.

The exhibit also showcases several examples of mid-century glassware that were popular from the 1950s through 1970s, such as iridescent “Carnival glass,” milk glass, Jadeite, and Fire King glass, which is similar to Pyrex, Barnett says, and “makes note of the popularity of glassware collecting.” Many of the items displayed were owned and donated by local individuals, including a variety of some 200 different shapes and sizes of table salt dishes — also known as salt cellars or open salts — from the collection of Agnes Lytton Reagan.

__

FAQ

‘A Century of American Glassware:

1870s-1970s’

WHEN — Through Aug. 10; 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday

WHERE — Rogers Historical Museum, corner of Second and Cherry in downtown Rogers

COST — Free

INFO — rogershistoricalmuseum.org or 621-1154