Contemporary portraiture exhibit Fragile Figures: Beings in Time highlights vulnerability and challenges notions of power

April Wallace

awallace@nwaonline.com

In ancient history, it was the wealthy and powerful who were enshrined in portraits. Those paintings were set in gilded frames, displayed in museums and hung in great halls, then later reproduced for textbooks.

But today it’s someone else who is the focus, and the perspective on what power is, and who is powerful has changed. That much is clear through 21c Museum Hotel’s “Fragile Figures: Beings in Time,” a group exhibition on contemporary portraiture on display in its Bentonville galleries through January 2025.

“Contemporary portraiture offers us insights about how we conceive, create and project identity in the world today,” said Alice Stites, museum director and chief curator at 21c Museum Hotels. Technology and social media has influenced how we view ourselves and others, which has also changed what makes a good portrait in the current age.

“There’s often a reversal of ideas of what power, being powerful looks like, versus what being vulnerable looks like,” she said. “Today, what we see … is reverence for the everyday person, for the vulnerable, for the unseen or overlooked.”

Many of the artworks in “Fragile Figures” look through a lens of art history, referencing notable, recognizable works while dealing with contemporary identity and current events. The effect is meant to connect the past and the present, historical and contemporary.

TRANSLATION

Yvette Mayorga’s works are a particularly good example of that, Stites said, because she is directly referencing paintings by 18th century French painter François Boucher. He was associated most often with the Rococo movement, which “came to be derided as excessive, decadent and too feminine.”

Viewers in Northwest Arkansas may have first seen Mayorga’s works at the Momentary contemporary art space, where Stites and 21c co-founders Stephen and Laura Lee first saw them before purchasing them for their collection and bringing them back to Bentonville.

Mayorga “is harnessing those ideas and associations with the Rococo and tying it to contemporary popular culture, specifically from Latinx culture from which she comes,” Stites said.

In the hanging sculpture titled “Until we meet again,” the Greek god Apollo reunites with his mother, modeled after Boucher’s “The Setting Sun,” only the figures are wearing Mexican Tribal boots. They also hold Mylar balloons with emojis, Hello Kitty and other signs of contemporary culture on them.

Mayorga’s “Resting Scrolling” is after Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour.

“Instead of a vision of the famous mistress of Louis the XV, the figure lying in bed scrolling on her phone is taken from a family photo of her sister,” Stites said. Then embedded with acrylic nails, Nike shoes, false eyelashes, plastic gummy bears, rhinestones and car wrap vinyl. “She is combining her own personal, lived experience with references to art history and to the lived experience of Mexican migrants from south of the U.S. border.”

DISTANCE

In the same room are a number of works by John Singer Sargent. Since several of his paintings are in the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art collection, Stites felt they would resonate for those in Northwest Arkansas.

Nearby is Nicholas V. Sanchez’s “La mariposa en Jalisco,” which also references a family background in Mexico. The portrait is based on Sanchez’s mother, a seamstress who made Flamingo dancer costumes, and the figure portrayed is enacting the traditional form of dance.

“A lot of the work makes these direct references to artwork that is very well known, but touches on things like migration, labor and consumerism and different forces that are shaping our identity today,” Stites said.

Video installation “The Space Between Us,” by Ana Teresa Fernandez is a “direct quotation” from René Magritte’s “The Lovers,” the well known surrealist painting in which two figures are caught in a kiss while their faces are enshrouded with cloth. In Fernandez’ video, the figures’ faces are covered in the same material used to make thermal blankets that migrants are given when they cross into the U.S.

“The reference is to the separation of people, families, lovers, parents and children at the southern border of the United States,” she said. That challenge to intimacy has connotations to the sociopolitical situation along our country’s borders. If the work strikes in you an emotional response of being fearful for them, know that’s the intended result.

“They are struggling to breathe,” Stites said. “She’s referring to the fear and desperation when they are forcibly separated or can’t reach their loved ones and can’t connect.”

REGAL

In Gallery One, near 21c’s ballroom, visual activist Zanele Muholi’s work “Ntozabantu VI Parktown” looms above the height of the average person. This portrait, from Muholi’s series Somnyama Ngonyama (“Hail the dark lioness”), is a wallpaper. Once it’s taken down, it cannot be reposted, said Veronica Inberg, museum manager at 21c Bentonville.

Growing up, Muholi was discriminated against and told they were unattractive. As a result, their work celebrates, acknowledges and honors queer people in South Africa, where, like many places in the world, it’s hard to be gay or LGBT, Stites said.

In the series Muholi took a self portrait each day using cheap materials as props. In this one, she’s wearing a children’s toy crown on their head, but looking “very regal and larger than life,” Stites said. “That’s a way of subverting and challenging (others perception of them), celebrating their vulnerability as power.”

At the front of 21c, in the window, is Marc Fromm’s sculpture, “Young Girl with Pet.” A floating wooden figure is holding a leash to stay attached to her pet, a puma. It references the 15th century painting by Netherlandish master Petrus Christus “Portrait of a Young Girl.”

Fromm’s young girl painted in three-quarters style, but looks antique since “parts look like they’re decaying, parts look burned … she doesn’t have an arm on one side,” Stites points out. The jewelry, however, looks cheap and contemporary and the puma as a choice of pet also points to a more modern era. It all references decadence, but in a different way than Mayorga’s works, Stites said.

A WHISPER

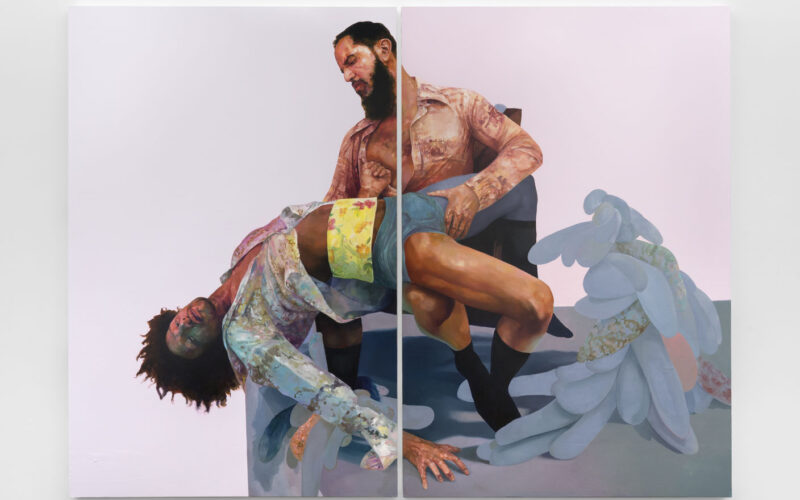

While some works, like the levitating girl, draw attention, others speak to guests more quietly. David Antonio Cruz’s diptych painting of two men is posed like Michelangelo’s Pietà, one draped across the lap of the other. Cruz is evoking the art of Balthus, the 20th century painter who often depicted women and girls posed in a sensual or sexual way.

But in Cruz’s work “what you don’t get is a hyper-sexualized, hyper-sensualized … image,” Stites said. Instead “what would typically be a heterosexual couple in a Balthus painting, he has really flipped the script. Instead of giving us an image of pain, like the Pietà, he’s given us a moment of tenderness, great intimacy.”

Its title “so let them eat asylum pink” is associated with the famous response by Marie Antoinette, King Louis XVI’s wife, to the news of poor and starving people in France. If they didn’t have bread, “let them eat cake,” she said, which signaled the decadence of the French monarchy.

The background of Cruz’s work is very pale pink. Stites wonders if it has any connotations to the color “Asylum Pink,” which has been used to paint the walls of jail cells of male inmates since it’s thought to decrease aggression. Within the context of that setting, where “relationships become more fluid than they are in the outside world,” Stites said she wouldn’t be surprised if that was an element to the choice of pink. “A lot of his work explores race and sexuality and queerness and intimacy.”

If viewers are not careful, they might miss Hans Op de Beeck’s “Night Time,” a video that animates hundreds of black and white watercolors that the artist created over several years after sundown, according to the 21c website. It’s in the video lounge, a nook that can be overlooked given that the door remains partially closed to keep the viewing quality high.

Stites describes “Night Time” as a lyrical, nostalgic evocation of the world of darkness and dreams. What it illuminates for her is that those forces, not just the political, social, economic and environmental ones, also shape our identities, how we see ourselves and each other.

Finally, to the far right of the lobby is a side gallery full of other works — portraits by Sebastiaan Bremer that have been applied with white ink dots to dissipate, almost pixelate, the image in a pointalistic way. In the center is Mat Collishaw’s video installation “Leda and the Swan.”

The sculpture based on Greek mythology sits atop a round mirror as light projects to it, then bounces onto the walls images of storm clouds and rain beginning. It brought to Stites’ mind the W.B. Yeats poem of the same name. It was written in 1933, before World War II, but predicts different conflict. Both the sculpture and the poem are about something historical, but the moment in the sculpture is before a crucial event takes place.

“This is a foreshadowing of Leda being impregnated with twins, one of who became Helen of Troy, whose abduction started the Greek and Trojan war,” Stites said. While it’s a meditation on human violence and power, it’s also about human fragility and frailty. Collishaw captured that by looking at the experience from three perspectives at once. “It’s a really interesting moment of time existing in the present, in the future and the past all at the same time.”