April Wallace

awallace@nwaonline.com

If you’ve not been lucky enough to be in the same room as Robert Johnson, Koko Taylor, Bobby Blue Bland or other blues icons, you might feel as if you have after visiting “A Cast of Blues.”

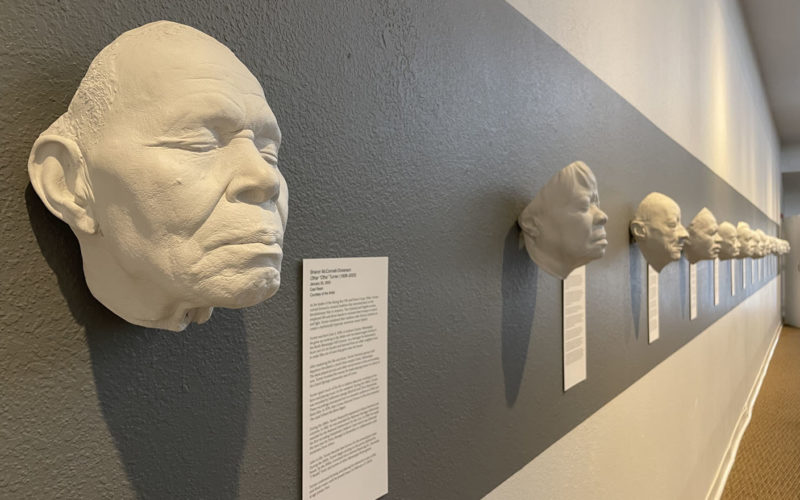

A total of 15 resin-cast faces now line a wall at 214 By CACHE, the gallery space at 214 S. Main St. in Springdale formerly known as the Arts Center of the Ozarks. The exhibition also includes a number of photographs by Ken Murphy featuring other musical artists from the Mississippi Delta.

The faces of blues legends are finely detailed, giving visitors a very clear picture of what they looked like the day the cast was made, something that goes well beyond the shape of each face. Strands of hair, beards, uniquely shaped ears—everything is exactly as it was.

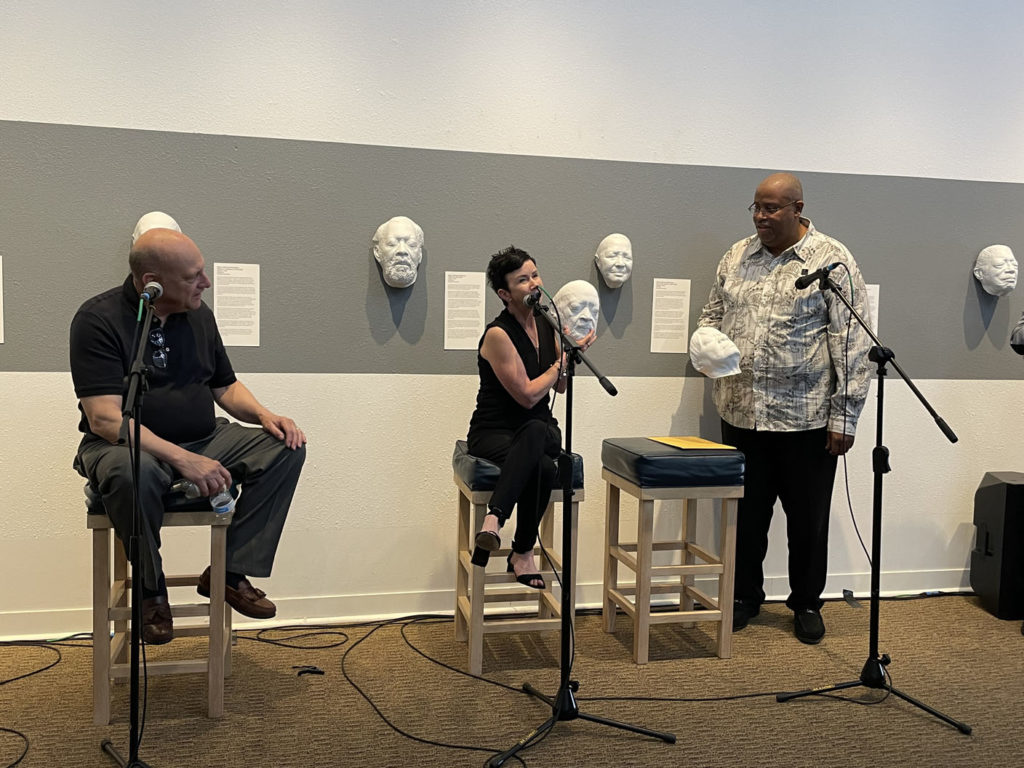

Orson Weems, executive director of the Music Education Initiative, helped bring the exhibit to Northwest Arkansas and says a group of physicians came to see the casts, and they were amazed at the level of detail.

“They were like ‘Wait a minute, I’m seeing veins, pimples and moles,’” Weems says. You can’t miss Bobby Blue Bland’s soul patch and thin mustache. Artist Sharon McConnell-Dickerson captured everything, Weems says, through her extremely fast alginate process. “When they look at these casts, notice that there are no air holes for a straw like you see in a mask or other casts, for them to breathe through; she did it so quickly.”

Altogether Dickerson created a total of 60 casts to memorialize blues musicians, these 15 in particular were curated by Chuck Haddix, music historian and director of the Marr Sound Archives, and have been touring since 2014 through the Kansas City-based Mid-America Arts Alliance.

“I like my masks to be touched,” McConnell-Dickerson says. “There’s something about the flesh that when you look in the mirror, you’re seeing a flat image. But the molding material captures every exact detail of your face, even pores, scars, the texture of the skin … it’s made three dimensional. There’s detail the human eye misses that you can only feel with your hands.”

McConnell-Dickerson made the casts over the course of 16 years after she lost her sight. She hopes her exhibit will cause various museums to rethink the accessibility of their exhibits. “A Cast of Blues” has an audio tour version that reads the text to visitors, which can be especially beneficial for children who aren’t reading yet or adults who have difficulty seeing and/or reading. The exhibit also places the items at a low enough level to encourage more people to touch them.

“Many times exhibits don’t consider younger visitors,” she says. “If you’re looking at a painting way up there, or in the case of the masks, you’d be looking up noses, which would be no fun for them.”

Placing them lower makes those in wheelchairs and others feel more included and considered, she says.

Getting the legendary musicians to agree to the process sometimes took a lot of convincing. As McConnell-Dickerson spent a little extra time with each of them for the casting process, she got to know more intimate parts of their personal history.

“The friendship forms after casting, having had an up-close and personal interaction where the subject is … allowing me to touch their face and cover their eyes, mouth, ears and (experience) sensory deprivation,” McConnell-Dickerson says. “There’s a lot of trust that’s extended to me … an exchange of energy.”

Weems says the cast faces help carry on an important part of the history of the South and of the blues. Bringing them to an audience who’s never seen them and may have very little handle on the influence of the blues is exactly what the Music Education Initiative is about.

“We’re sharing things people here would not normally get to see,” he says.

You don’t have to know anything about the blues to experience this gallery. Each cast and photo has a generous placard telling guests where the musician grew up and what led to their rise to fame. Many of them have connections to Arkansas and to each other.

Of the photographs, only one is directly next to the corresponding blues icon’s face, an image of the grave of Robert Johnson, the blues legend who’s known for his deal with the devil at the crossroads. His fans made many false headstones over the years, and the original one was only traceable due to a connection with the wife of a man who helped bury him, the caption reads.

Many of the descriptions shed light on the struggle the artists went through only to be recognized fairly late in life, or sometimes after their deaths.

Hubert Sumlin, for example, was raised in Arkansas and became Howlin’ Wolf’s guitarist for years. He was inducted to the Blues Hall of Fame just a few years before his death. But the fact that the Rolling Stones paid for his funeral points to his sheer influence on the music industry, Weems says.

Ruth Brown was another who quietly made a big impact but hardly made any money, he says, which is why many Black artists went on tour. At one point Atlantic Records was known as “The House that Ruth Built,” due to her music. It wasn’t until her appearance in “Hairspray” that Brown got proper recognition, Weems says, when she was awarded both a Tony and a Grammy.

There are a number of connections between Ken Murphy’s photographs of musicians to the icons on the walls. In one, “CeDell Davis and Lightnin’ Malcolm jamming at the Juke Joint Festival,” Malcolm sports a T-shirt that reads “Cedric Burnside,” referring to the artist who won a Grammy less than a month ago. Burnside’s grandfather, R.L. Burnside, is portrayed in one of the blues casts. In another photograph, an artist holds a guitar made by Super-Chikan Johnson, who creates unique and ornate instruments, while yet another photograph features the guitar maker himself with an array of his custom banjos and guitars behind him.

In a way, the photographs bridge the gap between the icons and the new blood.

“The way this is put together, you have the young and old in these,” Weems says. “They’re picking up from where the legends left off. Their torches have been lit.

“I want people to come and appreciate [this exhibit], honor and respect this music from these artists,” he adds. “To know that this (musical legacy) has to go on, it can’t be marginalized or minimized. Blues music is the root of music.”

__

FAQ

‘A Cast of Blues’

WHEN — 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday-Saturday through May 27

WHERE — 214 By CACHE, 214 S. Main St. in Springdale

COST — Free

INFO — facebook.com/musicedinitiative

__

FYI

In Concert

The Music Education Initiative will host Bobby Rush Raw: An Intimate Night of Stories & Songs at 8 p.m. May 20 at the David & Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History in Fayetteville. Doors open at 7 p.m.

INFO — musiceducationinitiative.org

__

FYI

More About The Music

You can hear tracks from the artists in the exhibit while walking through the gallery, since a playlist of Mississippi Delta blues is always on the speakers during open hours. But if you’d like to keep the music going, search for “A Cast of Blues NWA” playlist on Spotify. It highlights music from all the legendary blues musicians featured in the exhibit.

— musiceducationinitiative.org