Artists, residency explore present, past connections

JOCELYN MURPHY

jmurphy@nwadg.com

There is a well-known understanding within the art field, explains Pia Agrawal, that the work is only complete once an audience takes it in. For performance- or time-based work, though, that relationship is a little different.

Enter the artist residency, where sometimes, like at Bentonville multidisciplinary arts venue the Momentary, artists can continue to develop a project in a setting where the audience can react in real time. At least, that was the idea. The Momentary was supposed to continue its already extant residency program by physically hosting artists in the newly opened space for the first time beginning this month.

“We’re reframing a lot,” Agrawal admits. Agrawal is the Momentary’s performing arts curator and reveals that, in spite of the quarantines, shutdowns and cancellations of our post-covid-19 world, Momentary staff members were anxious to maintain the momentum of both the venue’s Feb. 22 opening and the scheduled artists’ already extensive labor.

A charcoal print from the “50 STATES: ARKANSAS” installation depicts the rail car where Wellington Stephenson and his live-in servant, and presumed lover, Jesse, lived in Harrison in the 1920s.

(Courtesy Photo)

“Quite frankly,” she goes on, “we’re reframing our relationship with art, with artists, how to interact with this work, how to have conversations. So that thought went into how we were shifting this residency. We wanted to still give communities around Northwest Arkansas — but with the virtual realm, really anywhere — the opportunity to understand the kind of work that’s being made by our artists.”

The result is a virtual residency with artists Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin as they progress the Arkansas piece of their prodigious installation series, “50 STATES.”

“We’re all going into this idea of virtual residency asking a lot of questions about, like, what is valuable in a virtual residency, when typically so much of what is being done in a residency is about that on-the-ground, in-person communication,” muses Margolin.

“It’s definitely a bit of an experiment,” his husband and artistic partner Vaughan chimes in. “How does this work? And what information do we need to transmit, and how do we do that? This will be a learning process for all of us, but how do we operate in such a way that we can actually communicate something of the story and the place and the feel to somebody who’s not there?”

What was originally scheduled to be a three- or four-week residency — involving bringing other collaborators from across the country to the Momentary plus work-in-progress showings — will now be a one-week virtual experience. Agrawal and other organizers on the presenter’s side are asking a lot of the same questions as the artists, she shares. How can online tools and the virtual sphere be used to connect the audience to the material in a meaningful way?

Artists Jake Margolin and Nick Vaughan’s “50 STATES: ARKANSAS” installation from their ongoing “50 STATES” series comprises massive images stenciled with charcoal. The organic but murky effect gave the creators a way to actualize the ambiguity around the core of the narrative the pieces are based on.

(Courtesy Photo)

Distilling the experience to one week will give both sides the chance to “interrogate the process,” Vaughan says, and evaluate not only how the situation works in its present state, but then how that progress can be translated to an in-person model down the road.

“We always work with these histories that have a way of wriggling out of what you want them to be, and you always kind of have to follow them wherever they lead,” Vaughan says of each installation. “So there’s something kind of poetically wonderful about the process, in this case, doing the same thing. It will be interesting to see what the structural shift in [the piece’s] development actually means on the back end in terms of how it informs what the content becomes, or the structure of the performance.”

As much as there is a unified mission behind the whole “50 STATES” series, Margolin shares, it is to figure out ways to connect untold, pre-Stonewall queer histories to what’s going on in current queer communities.

When Margolin and Vaughan set out several years ago to create a piece in Houston about cowboys and border towns, they quickly realized it was a narrative nobody was interested in. In spending time getting to know that and subsequent regions, the project has evolved to a long-term commitment to uncovering the erased stories of queer communities throughout history in every state.

“Everything we’ve been doing has had this incredibly clear paper trail,” Margolin explains of the installations they’ve created so far. “We’ve been able to go into archives and, sometimes as totally amateur anthropologists and amateur historians, we’ve actually added to the historical record.

“It has felt like if we’re going to be talking about these histories that are so contested,” he goes on, “where people have told us that our history either doesn’t exist or what we say about it is fantasy, anything [we present] needs to be on really solid ground historically.”

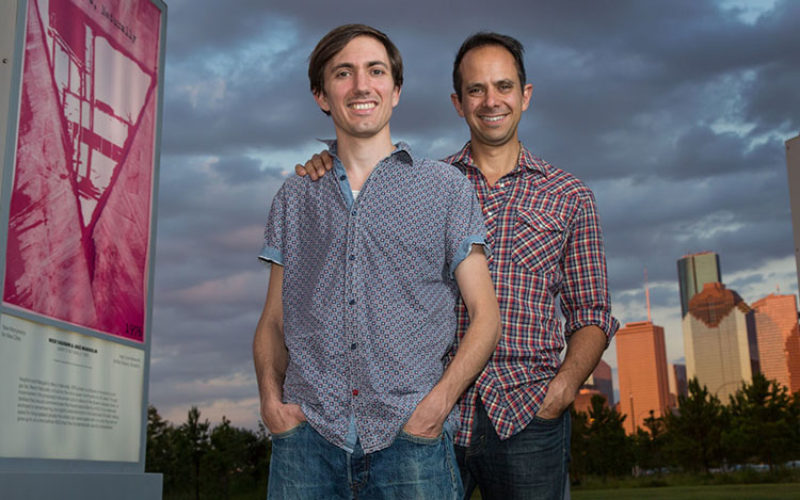

Nick Vaughan (left) and husband and artistic partner Jake Margolin were set to be the first artists in the Momentary’s residency schedule to physically work from the newly opened venue. Since the closure, the pair have been working closely with Momentary staff to arrange an effective and engaging virtual residency.

(Courtesy Photo/Janice Rubin)

So, with each piece, Margolin and Vaughan spend a substantial amount of time — usually several years — investigating the culture, the people and the buried tales of an area before they even land on a story to tell, much less the method by which the installation will tell it. That process changed, though, for the duo’s Arkansas piece when they were introduced to Wellington Stephenson and Jesse.

“There was a wonderful book by historian Brock Thompson called ‘The Un-Natural State’ that’s about the queer history, mostly in the mid-20th century, of Arkansas,” Margolin recounts of coming across the book during their research. “And at one point in the introduction, he mentioned these two people who have become the center of the Arkansas piece: Wellington Stephenson was the president of the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad, and his live-in servant, and most likely lover, whose last name we don’t know, but his first name was Jesse.”

The two men lived in a converted luxury railcar together in Harrison for several years during the 1920s while Stephenson was president of the railroad. So many details about the pair’s story were extraordinary, Margolin shares, but the further he and Vaughan got into their research, the more they realized they weren’t going to find that compulsory definitive paper trail.

“It was all hints and rumors,” Vaughan reveals. “But much like this statement in the Brock Thompson [book], it seems to be this thing that was known; it clearly passed between people.”

“The story itself was so spectacular,” Margolin picks up the thread, “and the ways that it intersected with the industrial history, the economic history, the racial history of the region were so exactly what we were trying to do with this entire project — which is to say that our community has been part of every strain of American history and American identity since its founding, and continues to be — that we felt like we really wanted to continue with it.”

Awareness that they had left the domain of “capital H history,” Margolin says, brought he and his partner to the realm of mythology, lore and ballads, which is how they landed on the medium to tell Wellington and Jesse’s story. The concept was to commission a series of ballads from artistic collaborators that would be presented alongside an installation of “mammoth” charcoal prints depicting murky images from the narrative.

Maybe the ballad will be completed by the end of the week and will be performed, Margolin says, returning to the residency. Maybe he and Vaughan will lead a virtual workshop offering insight into their process. The pair are still unsure exactly how the virtual residency will function, but both are optimistic about the piece’s continued unfurling in spite of these uncertain times.

“I think we operate with the sense that if you get the right people in the room working together — and in the case of Arkansas, it really is the right people — something wonderful will emerge from that. And you really have to trust that,” Vaughan concludes graciously.

__

FAQ

The Momentary’s

Virtual Artist-in-Residence

With Jake Margolin & Nick Vaughan

WHEN — Join a live conversation and Q&A at 6 p.m. May 4

WHERE — Hosted at themomentary.org/artist-in-residence-program or at facebook.com/theMomentary

COST — Free

INFO — themomentary.org, nickandjakestudio.com

__

Go Online!

‘50 STATES: ARKANSAS’

To hear more about the Arkansas piece, listen to a podcast with Jocelyn Murphy at nwadg.com/podcast.