April Wallace

awallace@nwaonline.com

Whether we think about it much or not, light often informs artwork in one way or another.

A new focus exhibition at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art explores the many ways that artists use light in their works.

Many of the sculptures have a lighting element, while the photographs require certain light in their development or use light as their main storyform when over- or under-developed. Still others are fascinating for the way they change depending on the light — reflecting it, absorbing it or changing color.

“The Light Fantastic” opened on Jan. 29 and will be on display through May 30. Curator Larissa Randall says the show does two things well: It showcases work from the museum’s collection not shown in a long time — or ever, in some instances — or frames them in a different way.

“We wanted a good balance of literal applications of light with more (abstract) ones,” Randall says.

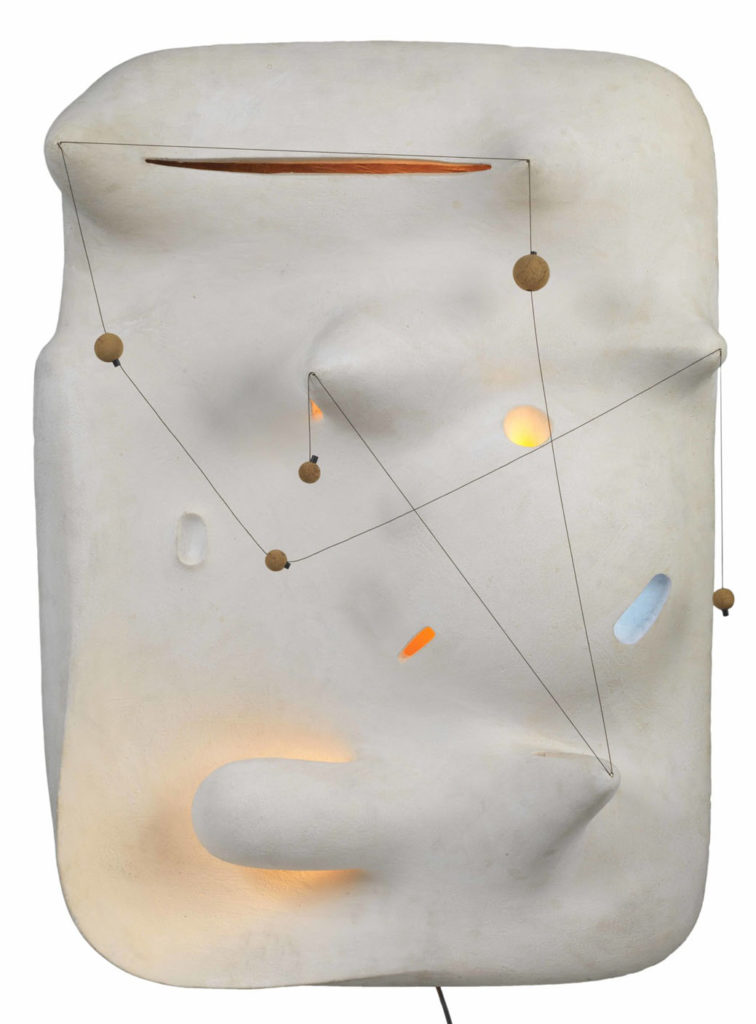

Isamu Noguchi’s 1943 sculpture “Lunar Landscape” is an example of a literal application, since it has electric lights embedded in cement. For each of the works selected, Randall asked herself how light played a role.

“That ambiguity alongside the more clear presences is where you can get rich dialogues about science and art in this exhibition, even with the photos,” she says.

Both of the Carrie Mae Weems photographs strongly feature a light hanging from the ceiling. It’s clear how the subjects’ proximity to it changes the mood of the piece. Randall says the exhibition illustrates how light can be an inspiration or medium, two very different things that are related.

Randall says the majority of the works by the 27 artists are light-based sculptures that are in conversation with the chosen photographs and other more abstract media. Just a week into the exhibition, she says initial viewers were delighted by the light elements of the sculptures.

Among the hidden treasures of Crystal Bridges is Jen Stark’s wall-based sculpture “Kaleidoscopic,” which has been in the collection since 2011 but never on view. This three-dimensional optical illusion protrudes in layers of pointed, spirally shapes — rainbow colored on one side and black and white on the other. And the best part, Randall says, is that it has a peephole.

“That’s the part that makes it perfect for this exhibit, [made for people] to lean up against and look into the sculpture that’s a kaleidoscope,” says Randall, who may have a special affinity for them since her grandmother used to collect them. “They’re all light and movement and colors and patterns rotating really quickly, giving a surprisingly delightful, disorienting feel that Jen Stark says takes the viewer to a state of transcendence, meditative and healing.”

In the same space as “Kaleidoscopic” is a special group of works, including the well-known white sculpture by Georgia O’Keeffe, “Abstraction,” which has always been on view at Crystal Bridges. It’s placed next to a neon sculpture by Dale Chihuly and James Carpenter that is lit from within. The neon vibrates in the glass and creates red space around it, coloring the O’Keeffe.

“Having the red light of the Chihuly bounce off the O’Keeffe sculpture impacts how you see it, and (we) experience light in the world in that way,” Randall says. “Even when it’s not explicitly about light, it affects how people experience art.”

Frequent or longtime visitors to Crystal Bridges may remember the exhibit of Chihuly’s glass works, which were displayed in 2017. It was among the most highly attended exhibits that the museum ever had. Randall says she is excited to get the neon sculpture out because it is an earlier, less familiar Chihuly work that was displayed 10 years ago.

“Some guests may not have known it existed,” Randall says. “It’s interesting to look at Chihuly, who is revered by our audiences. They may think ‘Isn’t he a hand-blown glass artist?’ It’s still impeccably blown glass, but full of neon.”

In the same monochromatic setting as the O’Keeffe stand two pieces by Frederick Eversley including “Blue Para,” a cast polyester piece, alongside “Kinetic Black Hole,” an Eleanore Mikus piece, epoxy and acrylic on wood.

“Each are from different time periods (but) have a similar look and feel,” Randall says. They’re all on a pedestal with neon red Chihuly. It’s meant to create an interesting effect of having both familiar and new objects all in the red glow.

Eversley is a unique artist to include, Randall says, because the conceptual artist’s casts and sculptures are formulated using math. He began his professional life at NASA as an aerospace engineer, but he continued his fascination with the celestial through art.

In fact, a number of the works deal with the natural sources of light, such as the sun, moon, reflection of their light, the stars and other cosmic events. The “space section” is anchored by Noguchi’s “Lunar Landscape.”

But Randall finds Eversley’s works exciting to express interdisciplinary experiences in more accessible ways.

“’Blue Para’ is a cast resin rendering of parabola, a math paradigm, something he thinks is beautiful but abstract,” she says. “Rendering it three dimensionally is interesting.”

Neither of Eversley’s works, “Blue Para” and “Kinetic Black Hole,” lights up but each is compelling because of how the light hits it. “Kinetic Black Hole” is a dark glass surface with a void in the middle, an O-shape reminiscent of a black hole.

“He’s using and playing with light shadows out of sculpture in a way that creates a central point,” Randall says. “The sculpture is wrapping around itself, through the void he creates.”

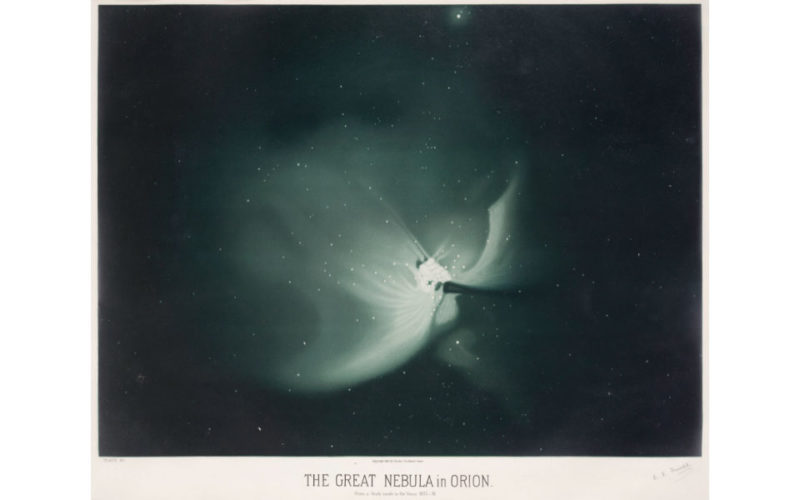

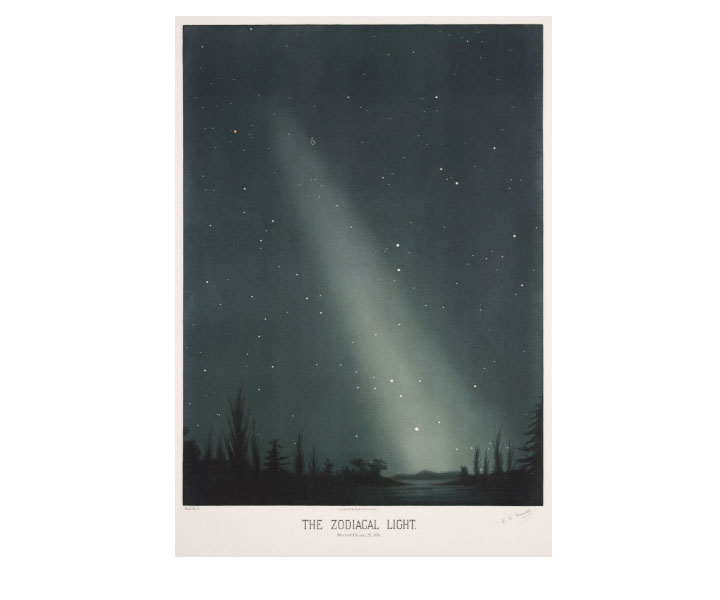

Etienne Leopold Trouvelot is another of the interdisciplinary artists Randall chose to place on view. Six of the French naturalist’s lithographs are included in “The Light Fantastic.” Trouvelot worked in the U.S. as a draftsman and print maker in the late 1800s when telescopes were becoming more readily available, but he opted to view events in the night sky without one. He made thousands of astronomical drawings from the naked eye.

Trouvelot’s “November Meteors”was produced in 1881, but it was based on his experience of watching a meteor shower 13 years before and rendering it artistically for more than a decade. His lithographs are prints from one leatherbound hardback volume that he produced for commercial sale as a souvenir object. He hand colored the large prints after the printmaking process.

“Instead of using a machine, he applied the colors himself and designed it until he got them right,” Randall says.

Some of Trouvelot’s prints give different context to another gallery mainstay, Agnes Pelton’s “Divinity Lotus.” Randall says his print of sunspots has a similar, abstract gooey look that brings out the luminescent effect in Pelton’s painting. That makes it less about her reputation as depicting spiritual realities and more about her skills.

Other familiar pieces stem from the 2014 “State of the Art” exhibition.

Before leaving the exhibit, Randall hopes guests will take along the wall of quotes created from interviews with people in the light industries. Filmographers, optometrists, botanists and others talk about the effect of light on their subjects and work.

For individuals with light sensitivity, Randall says, there are other visual experiences and three-dimensional printed touchable items and even objects to get under.

“It casts a wide net,” she says. “We wanted to make sure we have something for everyone.”

__

FAQ

The Light Fantastic

WHEN — Through May 30

WHERE — Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 600 Museum Way in Bentonville

COST — Free; no ticket required

INFO — 657-2335, crystalbridges.org