Nelson Hackett exists only in accounts written by other people. There is no record of any of his own words. Neither is there an image of his face. But Hackett’s story illustrates how one man’s legacy can be researched and resurrected 180 years later.

Hackett, who was an enslaved resident of Fayetteville in 1841, was the topic of a Sandwiched In program by Dr. Michael Pierce Feb. 17 at the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History via Zoom. Pierce, an associate professor of history at the University of Arkansas, is from Columbus, Ohio, and earned his doctorate in U.S. history at Ohio State.

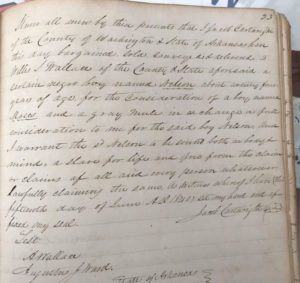

Bills of sale, recorded in the Washington County archives, probably refer to Nelson Hackett.

(Courtesy Image)

“While in grad school, I met my wife and followed her to the University of Arkansas after she took a position teaching [and] researching Russian history,” Pierce picks up the story. “The University of Arkansas history department put me to work teaching Arkansas history and helping edit the Arkansas Historical Quarterly.

“As a labor historian by training, I have always been interested in the ways that Americans work and the systems in which they produce goods,” he continues. “The study of slavery is central to labor history — not only because enslaved people were forced to work but also because slavery affected other forms of employment.”

Pierce stumbled on to the story of Nelson Hackett when he read Roman Zorn’s “An Arkansas Fugitive Slave Incident and Its International Repercussions” in Volume 16 of the Arkansas Historical Quarterly, published back in 1957.

“I was drawn to Hackett’s story because it began here in Fayetteville, but its effects reverberated throughout the entire Atlantic world,” Pierce explains. “Hackett provides historians a compelling way to teach complicated ideas about slavery, the power of enslaved people, and the ways that fugitives forced the Atlantic world’s diplomatic community to deal with those who remained unfree in an age of increasing personal liberty.”

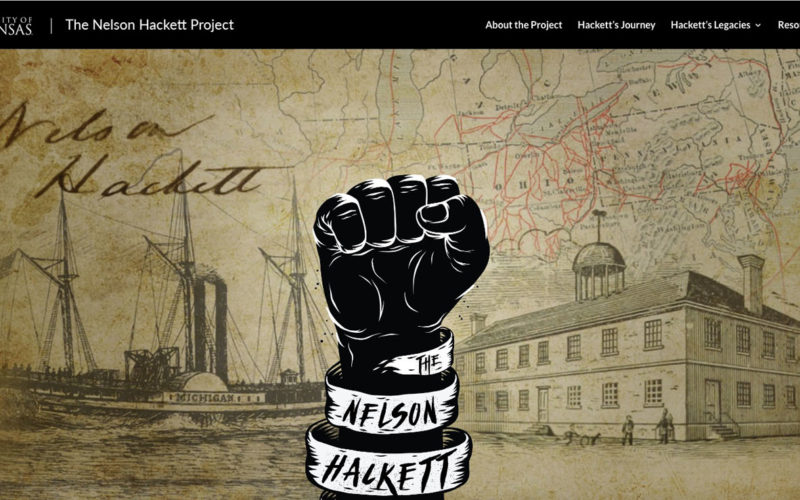

According to the Nelson Hackett Project website (nelsonhackettproject.uark.edu) Hackett fled Fayetteville in July 1841, presumably headed for Canada.

“There are conflicting accounts of Hackett’s departure,” the website relates. “Alfred Wallace, who claimed to own him, accused Hackett of leaving Fayetteville while Wallace was away and of stealing a race horse, saddle, coat, 100 £ ($500) in silver and gold coin and a neighbor’s watch on the way out of town. Abolitionists later disputed Wallace’s version of Hackett’s escape. What is not in dispute, though, is that Hackett’s flight took him across the state of Missouri, through Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan, across the Detroit River and into Canada West (now the Province of Ontario), where the last remnants of slavery had been abolished in 1834.”

Arriving in Canada on Sept. 1, Hackett surely thought he had found freedom. He was to be proven wrong. Wallace tracked him down and demanded his extradition back to Arkansas on charges of theft. Supporters of slavery spoke up on Wallace’s side, while abolitionists called on Canada to give Hackett his freedom.

“The conflict was settled by the governor general of the Province of Canada, who declared that the fugitive’s guilt and the need to discourage such men from putting down roots in the province required him to return Hackett to Arkansas,” the website continues the story.

“In February 1842, Nelson Hackett became the first and only fugitive from slavery that Canada sent back to the United States, making abolitionists fearful that slave owners would fabricate claims of theft to secure the return of runaways,” the website explains. But abolitionists refused to let Hackett’s extradition set a precedent and demanded promises from both Canada and Great Britain “to prevent the future return of fugitives like Hackett.”

“Hackett’s escape transformed slavery by putting into motion the events that ensured the Canada would remain a safe refuge for those fleeing slavery in the United States,” says Pierce. “During the 1840s and 1850s, the persistent flight of enslaved people to Canada was one of the main drivers of the sectional crisis that ended in civil war and abolition.”

The Nelson Hackett Project, based at the University of Arkansas, has resurrected the story of one enslaved resident of Fayetteville who fled to Canada in 1841. Read more at nelsonhackettproject.uark.edu.

(Courtesy Image)

Pierce says telling Hackett’s story was made easier by the advances of digital historical research. But the absence of Hackett’s own words — except perhaps in a deposition submitted to Canadian authorities — “is rooted in the racism that undergirded chattel slavery and created most of its archival record. Only Hackett’s actions themselves — his flight from Arkansas, journey to Canada, and possible escape upon his return to Fayetteville — tell us about his motivations and desires, offering an alternative to the written record and deeper insight into his full story.”

What happened to Hackett in the end remains unclear. Some records say he was publicly whipped upon his return to Fayetteville, then sent to Texas to be worked to death.

“Historians sometimes have to live with a great deal of uncertainty,” Pierce says. “There are things about the past that we will never know, like what happened to Hackett. But in this uncertainty there is hope — hope that Hackett found a way to live his life as a free man.”

Pierce hopes talking about Hackett helps “people recognize the agency and humanity of those people who were enslaved.” And he thinks the story is not yet concluded.

“Moving forward, the Nelson Hackett Project hopes to continue research into Hackett’s life and legacy,” Pierce says. “There are several archival collections — especially the papers of abolitionists — that might contain additional material. As these collections are searched and material is found, it will be incorporated into the website.”

FYI

Hear! Here!

Listen to Dr. Michael Pierce talk about the Nelson Hackett Project with Free Weekly Editor Becca Martin-Brown in a podcast at nwaonline.com/214HackettPodcast/